After the Annual Event in Ljubljana, We Continue the Path of Integration in Belgrade

Business Forum of Economic Integration

editor

The Adriatic team

The Institute for Strategic Solutions (ISR), together with the Serbian Chamber of Commerce, is organizing a business forum to present the 10th issue of The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022. The Belgrade event is a continuation of ISR’s annual Ljubljana meeting that took place in January.

The business forum which will host a CEO round table will be held on February 2, 2022, at the Crowne Hotel in Belgrade.

As in Ljubljana in Belgrade, too, we will pay attention to the economic integration of the Western Balkans. The event is open to the public and is intended for those who follow the political, economic, and financial spheres – for everybody with an active interest in the Western Balkans region. See a full program of the event below.

If you want to join us in Belgrade, let us know at info@isr.si

Cooperation Leads to More Resilience and Economic Strength

ISR Annual event

editor

The Adriatic team

"Integration: The Road to a Sustainable Economy" was the focus of this years’ annual forum organised by the Institute for Strategic Solutions (ISR). Traditionally taking place in January, the event sees important decision-makers present their views on the economic and wider social challenges for the next twelve months ahead, both in Slovenia and the wider region. The 2022 edition explored the opportunities for Western Balkans countries to strengthen their economic cohesion and integrate into European connections.

“If it wasn’t for the EU, the fight against covid-19 would have been much harder. We found it easier to get funds, vaccines, and other help, to fight the epidemic. Therefore, it is also in the strategic interest of the Western Balkans countries to be connected to the EU. At the same time, it also is an opportunity for the Slovenian economy, which participates in the implementation of development projects in this region and thus grows,” remarked Anže Logar, Slovenian Minister of Foreign Affairs, in his keynote address to ISR’s 2022 forum.

After the pandemic had forced ISR to go fully digital in 2021, the 2022 event successfully reverted to the in-person format, enabled by high health standards at the venue and on-site testing. The event also saw the launch of this year’s edition of The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight. It is packed with up-to-date content on geopolitics, the economy, sustainability, and new business models, offering useful and useful reading to decision-makers in the Western Balkans.

“The year 2021 only further strengthened the realization that we can overcome the pandemic situation only through close cooperation, both economically and at the level of society at large, and with trust in institutions. This is the only way that reliably leads to economic recovery and prosperity. If we focus on the Western Balkans, integration, cooperation and closer integration into European connections are steps without which the region cannot grow and strengthen,” remarked Tine Kračun, ISR’s Director and Editor-in-Chief of The Adriatic. He highlighted how sustainability, which the EU had identified as the heart of its future development, was also one of the emerging challenges to regional integration.

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

LIVE STREAM – The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

Live stream - Annual event

editor

Annual event presenting the latest issue The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

Institute for Strategic Solutions (ISR) traditionally organizes an annual event to present the new issue of The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022. We will focus on the economic integration of the Western Balkans, so this year’s event is entitled Integration: The Road to Sustainable Economy.

You are invited to watch the event live above. The event is held in the Slovenian language.

We thank our supporters

Entrepreneurial Success Largely Depends on a Supportive Environment

editor

Jan Tomše

JOURNALIST AT THE ADRIATIC

How the Slovenian support environment for start-ups is connecting with the Western Balkans

Slovenia boasts an extremely diverse support environment for start-ups and fast-growing companies. Although it is a small country, Slovenia generates an enviable number of innovative start-ups, a large proportion of which achieve globally successful breakthroughs. The state plays an important role in the development and the global competitiveness of the supportive environment, both through substantive backing and funding.

“Innovative ideas with high added value, which are essentially high-tech, green, sustainable, socially responsible, and digitally supported, lead to the creation of high-quality jobs, economic growth, global competitiveness and, last but not least, can provide answers to the most complex social and other challenges of humanity.”

Tomaž Kostanjevec,

director of SPIRIT Slovenia, the public agency that exercises programmes for promoting entrepreneurship.

In addition to talented individuals, access to capital is essential for the development of such ideas, throughout all stages of a company’s development. Global rapid growth often requires investments of millions of euros. “Banks do not usually finance such projects due to the high risk involved, so venture capital is key. Without start-up investment and access to capital, even the most promising ideas have little chance of coming to life,” says Kostanjevec.

Information, workshops, idea assessment, mentorship

One of the important roles in increasing the chances for good ideas to take off is played by SPIRIT Slovenia, a public agency under the auspices of the Ministry of Economic Development and Technology. The agency has been running several programmes to promote entrepreneurship since the very beginning of the creation of a supportive environment more than a decade ago.

SPIRIT Slovenia currently co-finances 21 innovative entities promoting entrepreneurship in all Slovenian regions. They also provide information, workshops, business idea assessment and diagnostics, mentoring, and advice to innovative entrepreneurs, including potential entrepreneurs, as well as accelerator programmes and competitions for best business ideas, activities to strengthen the entrepreneurial community and other related activities.

“The arrival of the corona has exposed many social structural weaknesses that were previously unconscious or more hidden. Overnight, it became even clearer how important are innovation, sustainability, green approaches, social responsibility, and adaptability to new circumstances. Companies have been forced to innovate to a higher degree, to think outside the box, to adapt their business models, and to digitise,” remarks Kostanjevec. He adds that start-up investments are important not only in stimulating and bringing about the innovation born in start-ups, but also in helping existing companies innovate and adapt their business models. This is where start-up investments can play an important role, provided, of course, that it is not about solving unpromising situations, but about newly discovered opportunities,” says Kostanjevec.

From Slovenia to the Western Balkans

Entrepreneurial success requires a lot of support on different levels: at school, in acquiring knowledge, and in developing both creativity and an entrepreneurial mindset. Later on, when developing an innovative idea, mentors and advisors are essential. Companies need proper interlocutors, often with access to research equipment, capital, business premises, and other infrastructure. “Same as with top athletes, it is difficult for entrepreneurs to succeed on their own, which is why support is a must. Without the right support, there would be significantly less entrepreneurial success,” says Kostanjevec.

He gives the example of how entrepreneurship is supported in the early stages by SPIRIT Slovenia. “We have two strong plaftorms. The first is the national SPOT system, which brings together a range of support services offering free help, information and advice to businesses. The second platform is SIO, which connects business and university incubators, accelerators, technology parks, and other environments that enable the creation and growth of new businesses.” More than 120 mentors and 200 business advisors are connected to SIO centres. Each year, they organise more than 600 workshops, lectures, startup weekends, informal meetings and other training events, supporting more than 100 entrepreneurs on their entrepreneurial journey.

“We can proudly say that SPOTs and SIOs represent a solid foundation and a central infrastructure for the creation of new breakthrough entrepreneurial stories in Slovenia,” says Kostanjevec.

But SPIRIT Slovenia’s activity does not stop outside domestic borders. They are also actively involved in the entrepreneurial environment of Western Balkans countries. “We are aware that we should not operate in a bubble, but cooperate internationally. That is why we have strong links and cooperation with the countries of the Western Balkans. Not only at an umbrella level, but also at the level of companies, organising delegations, visits, promoting international trade … It is important to underline the importance of sharing knowledge, good practices and connecting entrepreneurs. The Slovenian entrepreneurial ecosystem, including SPIRIT Slovenia, has the desire and ambition to see even more of this kind of networking in the future,” explains Kostanjevec.

“In the Western Balkans, we can provide good entrepreneurial support to innovative entrepreneurs, and we can also find niches where we are already leaders. We are very proud that Slovenia is becoming an European leader in the number of the so-called ‘hidden champions’ – many Slovenian companies are world leaders in specific areas in high-tech and niche technologies,” says Kostanjevec, adding that this knowledge, case studies, technology, along with all the support services, are now becoming increasingly available the Western Balkans, to entrepreneurs and to individuals striving to enter the world of entrepreneurship.

THE ADRIATIC

This article will be published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

€140 Million for Resilient and Improved Operations

editor

Jan Tomše

JOURNALIST AT THE ADRIATIC

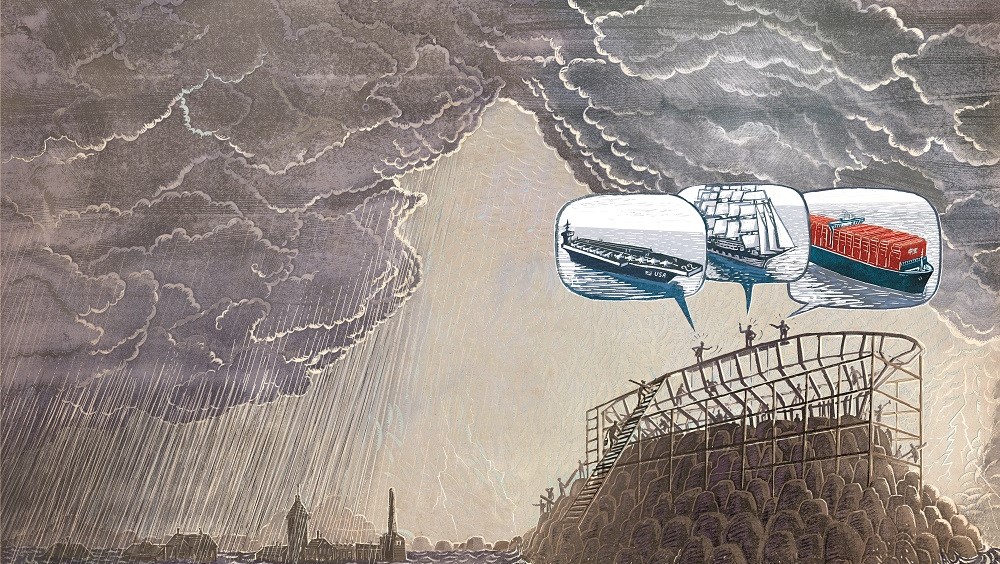

While the covid pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of many market players, some business operators were able to improve position despite uncertain times. In the logistics sector, the fortunes of the Port of Koper have risen.

The covid pandemic has had a significant impact on the logistics sector around the globe. The Western Balkans is no exception in this regard. Within what is a relatively low-margin industry, logistics players rely on well-established networks to streamline operations. Since the sector is highly competitive, logistics operators need to constantly invest in upgrading their business processes, facilities, and infrastructure.

While many companies struggled to keep their head above water, others were lucky enough to be able to improve their business position in these harsh times. Investing in better infrastructure, for instance, has proved to be one of the most important drivers of post-pandemic recovery. For the Slovenian enterprise Port of Koper (Luka Koper), building better infrastructure was to good an opportunity to be missed.

Despite the covid situation, the operator of the multi-purpose port of Koper completed two years of intensive investment. In 2020, they put almost €68 million in the new infrastructure and equipment, and in 2021, planed investment amounted to €75 million. A significant proportion of these upgrades are focused at the container and automotive segments. The company has one main goal: to improve the effectiveness and the quality of business operations, so as to be more competitive and attract new partnerships.

Among top automotive ports in the Mediterranean

In 2020, the company implemented two major improvements aimed at the automotive segment. A new dedicated RO-RO berth was opened, and a new railway access platform was built on the north-east side of the port. The year 2021 saw the conclusion of two additional projects. A new, third truck gate was opened, and a new garage with the capacity of 6,000 cars was completed in May.

With an annual throughput of over 600.000 cars, the Koper car terminal ranks among the top automotive ports in the Mediterranean.

In June 2021, the company inaugurated a 100-meters extension of the container terminal quay. The goals, however, are not fully achieved yet, with new stacking areas due for completion in 2022. This will raise the annual capacity to 1.5 million TEU. “In late 2022, two additional super post-panamx STS cranes will be installed at the new container. With almost one million of TEUs handled, Koper is the first container terminal in Adriatic,” explains Sebastjan Šik, head of public relations at the Port of Koper.

In late 2022, two additional super post-panamx STS cranes will be installed at the new container. With almost one million of TEUs handled, Koper is the first container terminal in Adriatic,

Sebastjan Šik

Head of public relations at the Port of Koper

The new railway line, a new chapter in the port development

A major contribution to Port of Koper’ competitiveness will be the new railway line. Finally, construction works on the new rail route between Port of Koper and the hinterland began in May 2021. According to the project timetable managed by the state-owned company 2TDK, the due date for the 27 km-long section is 2025, while the track is expected to be operational in 2026. Šik describes the project as “the new chapter in the port development”, adding: “With this modern and reliable railway connection, a new chapter of business opportunities and development is opening up for Slovenian logistics and for the countries who rely in their supply chain on the Port of Koper.”

THE ADRIATIC

This article will be published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

What Is Happening With Energy Prices?

editor

Adriatic staff

The global market price of electricity has risen by 175% in the last year.

No later than 10 December, electricity providers must publish new price lists for business users (applies to all providers) – these prices will be the same as global market prices. In Slovenia, there is a significant share of such companies (estimated at 40%) that have not yet secured electricity prices for the next year – for them, the cost of electricity will rise by a factor of 2.5 compared to 2021.

Energy sources abroad

Some economists expect that the problems with the procurement of (various) energy raw materials will continue strongly next year. However, demand for a sharp post-pandemic rebound will slow down, reducing price pressures. Some providers do not even want to change the current situation as this would lower their sales prices. In this context, current price levels suit Russia and some other producing countries, which treat energy as their strategic good. Much will also depend on supply constraints elsewhere: if talking about oil, the US surely deserves a mention. Slower supply is also expected for other energy sources such as liquefied petroleum gas.

Rising energy prices also raised the price of crude oil

In October, crude oil prices rose by more than 12%. The increase is due to rising energy prices in Europe and Asia. An important factor in the price hikes was the mass transition from gas to oil energy sources.

Although the price of oil continues to rise, the situation may change, the IEA said.

It will continue to strengthen in the future to meet the growing demand for oil, which has still failed to catch up to pre-crisis levels. Refineries are becoming more lively after the autumn maintenance work, while end consumers are stepping up demand for petroleum products by opening borders, reviving mobility and increasing vaccination coverage. New viral outbreaks around the world and a slight slowdown in industrial activity will – together with higher oil prices – affect the way demand develops in the coming weeks and months. Opec predicts that demand will be higher next year than in 2019 – it will exceed the level of 100.1 million barrels per day.

Get Ready for The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

New edition of The Adriatic

editor

The new edition of The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022 is in the making.

This time we are covering a wide range of topics for you to read. In Geopolitics, we will bring out our annual overview of the Western Balkan countries. How far have they made it in the EU integration process, and what are the three top risks they are facing in 2022? In the Business section, we will delve into the strategic role of logistics – from ports to railways. Building a resilient economy will be the main topic when speaking about the common economic environment in the region as an opportunity for the countries in the Adriatic region and their path towards EU integration. The Living section is covering topics such as regional startups, a new contemporary art venue in Ljubljana, and much more.

The new edition of our annual magazine The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022 will be launched in the second half of January 2022 in Ljubljana. The accompanying event will feature a round table with key decision-makers in Slovenia.

In 2 February 2022, we will host a conference in Belgrade together with the Serbian Chamber of Commerce. We will bring together Slovenian and Serbian businessmen and prove that integration is the path to regional economic resilience.

We are inviting you to follow us and stay tuned for further information.

Your Adriatic team

We thank our supporters:

The CEO Who Cut His Salary to Save the Company

editor

Haris Buljubasic

JOURNALIST AT THE ADRIATIC

Have you ever heard of a public company boss who cut his own salary while rising the pay of non-qualified workers?

Naser Rujanac, from the city of Donji Vakuf in Bosnia and Herzegovina, did exactly that while fighting to save a public utility company from closing down during the pandemic. In a country where many see a job in the public sector as a good source of private money, stability, and comfort, Naser forged a plan and saved the company, alongside the jobs of his employees.

„I think that the salary of the former director was too high, considering the condition of the company“, says Naser, who became the acting head of the company Gradina in July 2021. He found a company burdened with huge debts to the tax authority and had to act promptly to make sure company is up and running.

Motivating the most hard-working ones

Naser faced a company in dire straits. Bank accounts were blocked, and the company could not even secure gas although it was crucial for running machinery. First, he drew up a debt reduction plan and reached an agreement with the tax authority on the repayment schedule. But he also needed to keep his workers motivated, so he managed to secure them and pay rise.

„These are workers who work in all weather conditions. The company depends on their contribution, and we should appreciate that. There was too big a difference between the salaries of the company’s management and non-qualified workers“, Naser told The Adriatic.

The new boss also managed to find a way to settle the company’s old debt the employees. It required many cuts, he says, starting with small ones like cutting the business phone allowance.

“Eventually, every effort and sacrifice for the benefit of the community pays off many times over.”

Many in this country dream of a position like Naser’s. Jobs in the public sectors are seen as a good and a secure source of decent money. However, Naser insists that a public job means a chance to do something good for the local community.

He is well-known in the local community which has elected him a few times to municipal council. At first, Naser was member of the SBB political party (Union for a Better Future of Bosnia and Herzegovina), but later become an independent candidate. Having already worked in the company he is heading now, he knew very well what the problems were.

Will the hard work pay off?

Just like with many other public companies in Bosnia and Herzegovina, Naser is only an acting director. Whether or not he will be reappointed for a full four-year term, will be decided in January 2022. But he already has the support of the workers’ union which has recognized his efforts so far.

Naser is confident about achieving his goals. He said: “I could easily achieve the set goals. Unforeseen situations do happen, but with good organization, we will succeed.” In two months, Naser would know for sure.

How Big Data Contributes to Environmental Sustainability

Environmental sustainability

editor

Maja Nikoloska

JOURNALIST AT THE ADRIATIC

Climate change is one of the biggest challenges of our era. As a driving force behind the information revolution, Big Data has an enormous potential in improving environmental sustainability. Every day, millions of new data sets are being generated in the world, which has an important role in finding a successful solution to this global problem.

Data sources are becoming more and more complex and Big Data is being generated from different networks, devices, sensors, the web, social media. Basically, all human activity can now be registered, and the same is true for all natural phenomena occurring around the world. By analyzing relevant data sets and finding the right patterns, future outcomes can be predicted, and with proper use, real-world problems such as environmental sustainability can also be solved.

To face the challenges in the environment, many environmental organizations use Big Data analytics solutions to improve their practices and refine their methods. The main sources of sustainable data are satellite photos and public databases, requiring public-private collaboration – with collecting, crossing and relating data from physical components such as droughts, earthquakes, rains, fires, with data on social components such as light intensity per household, telephone calls, social networks activity and use of transport. Further analytics can show how all these data can help avoid geopolitical conflicts, understand human behavior in case of natural catastrophes or humanitarian crises and understand the vulnerability and the resilience in different situations.

Analytics play a major role in achieving a better world for everyone

To improve decision-making in both the public and private sectors, Big Data can also be used for ecological forecasting. Life Under Your Feet, for example, is a tool that gathers data from satellites on the global variation of humidity or temperature. This way the study of climate change is more precise. Near real-time tracking of the data can be beneficial for environmental change, in order to make actions consequently to the changes within a similar temporal scale, which is often hard to do since there is very little time. By identifying the patterns of suspicious behavior on time, the time frame of the reaction is extended. These kinds of early warning systems, are somehow the way to improving outcomes for nature and people. Furthermore, the Ocean Observatories Initiatives, monitor the ocean activity and do real-time analysis to predict the risks of possible tsunamis or seabed movements.

With integrating Big Data into government policies, better environmental regulation is ensured. Using the latest sensor technology, governments can easily acquire real-time reporting of environmental quality data. This data can be used to monitor the emissions of large utility facilities and if required put some regulatory framework in place to regularize the emissions. In order to achieve the required results, companies are granted complete freedom for experimenting and choosing the best possible mean. For example, India Night Lights collects data from the light intensity in India to know exactly where the energy consumption is, or the increase or decrease of the electrical use.

Every year more and more data is being recorded, so with no doubt, Big Data analytics plays a major role in achieving a better world for everyone – also by monitoring and controlling future environmental changes and sustainable development.

Go Greener, Get More Added Value…

Business

editor

The Adriatic Staff

At the beginning of October, Ljubljana hosted business conference Exporters 2021: How Agile is the Slovenian Economy in the European Union, organized by the media outlet Delo and the Institute for Strategic Solutions.

At the conference, panellists reflected on the opportunities the European market offers for the Slovenian economy, as well as how to increase the added value in Slovenian exports and how to achieve a digital and green transition that will address the challenges of the coming years.

»Slovenia is a small story in the world, we depend on global forces. At the global level, there is a race between the US and China. At the local level, the opportunity for us is entrepreneurial ingenuity and how we can respond to what is happening. Europe will have to become more integrated and stand up to other superpowers. Slovenia needs to engage in lobbying at EU level and, above all, look for business opportunities within this environment,« said Domen Prašnikar, founder and CEO of Valior.

More technology for more user-friendly solutions

»Is the consumer willing to pay more for something that is made just for them? Rather than doing more for less money, we should use technology to create products that are made specifically for the consumer,« added Zoran Stančič, Associate Adviser at the European Commission’s Directorate General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology (DG CNECT).

As Zdravko Počivalšek, Minister of Economic Development and Technology, said in his address, Slovenia has created the conditions for restructuring the economy, which will bring new and better jobs.

Tine Kračun, Director of the Institute for Strategic Solutions (content partner), Aleš Cantarutti, Director General of the Slovenian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and Stojan Petrič, Director of the media outlet Delo attended the conference.

Battling uncertainty with the single market

Photo: Jože Suhadolnik/Delo

Keynote speaker Kerstin Jorna, Director-General of the European Commission’s Directorate-General for Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs, highlighted the strength of the Slovenian economy, including tourism. The EU has learnt through the crises that it needs to strengthen the resilience of the single market, and that SMEs are particularly important as they are the backbone of the European economy… The single market is crucial in uncertain times, she stressed.

The three panels brought together excellent panellists who highlighted the need for Slovenia to further strengthen its productivity, to make better use of global events such as sporting events it hosts, and to invest more in research and development.

Slovenia’s economy also has its strengths, which are recognised by international markets, obviously. As Bojan Ivanc, Chief Economist at the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia (GZS), said, »We have a lower price for a product or service than our competitors, while at the same time we ensure adequate product quality and qualified staff. The uniqueness of products and services and the flexibility to respond to customers’ wishes are also advantages in favour of our exporters.«

Still challenges to going green

Gorazd Justinek, Assistant Professor of International Political, Economic and Business Relations at the Faculty of State and European Studies. He believes that the role of Slovenian economic diplomacy in third markets, outside the EU, is relatively weak, and it should therefore be strengthened.

However, Slovenia has a good foundation in the area of digitalisation of companies, said Davor Jakulin, CEO of ATech. Domen Prašnikar agrees: »Slovenian companies are cutting costs and making the transition to digitalisation. However, I see more challenges to go green,« said Prašnikar.

THE ADRIATIC

This article is part of The Adriatic Journal: Strategic Foresight 2021

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.