Bringing the Best to Society

5G

editor

The Adriatic in partnership with Telemach

The next-generation of mobile networks brings unprecedented opportunities for development and progress.

What can a 5G mobile network do for its users? This is a question posed by professionals and laypersons alike; it stirs the imagination. The future will provide the exact answer. In the meanwhile, it is already clear that 5G delivers higher speeds, improved responsiveness and more bandwidth.

For consumers, the new generation of mobile technologies represents an evolution. The things they can do on their smart device already, with the help of 5G, will be done faster, more efficiently, and with extended capabilities. But the endless possibilities offered by 5G will be much more felt by businesses. We will see a revolution in machine connectivity with the Internet of Things at the heart of the next-generation mobile network. The significantly higher speeds enabled by 5G will result in minimal latency, which is a very important factor when it comes to communication between different devices, i.e. the Internet of Things (IoT).

This will drive the development of smart industry, agriculture, and communities as a whole. Together with the Internet of Things, 5G technology can improve energy efficiency, reduce greenhouse gas emissions and drive more efficient use of renewable energy. It can help reduce air and water pollution, reduce food waste and protect wildlife and the environment.

As to public safety, 5G brings advantages to firemen and rescue teams, making it easier to fight fires, rescue people from mountains and even locate missing people or pets. It also enables the digitalisation of healthcare services, remote patient treatment and specific complex solutions such as remote diagnostics, remote consultations and remote surgeries. The benefits of 5G will be felt across all aspects of our lives.

The roll-out of 5G in the economy will be gradual. However, in a few years, we can expect an explosion of activity we haven’t seen in a long time.

“5G is, or will be, a powerful driver of digital transformation. It is the first mobile communications system that is not primarily designed for people but is machine-centric. It will revolutionise machine-to-machine connectivity and put Internet of Things at the heart of the nextgeneration mobile network,” says Zoran Vehovar, Chief Technology

Officer at Telemach.

TELEMACH IS THE FIRST TO DELIVER A TRUE 5G EXPERIENCE

The benefits of 5G will be felt across every aspect of our lives and in Slovenia, Telemach was the first to introduce a gigabit network with a true 5G experience. At the end of 2021, its 5G network is already available in more than 50 major cities across Slovenia and the company is accelerating its roll-out. “We’re building the 5G network aggressively. We want to make the most of the frequencies we have bought atauction, as quickly as possible. We are deploying additional equipment everywhere and have far exceeded our original plans for this year. We’ve accomplished much more than we had planned at the start,” Vehovar adds.

This is helping the company to rebuild its technological foundations, create a competitive advantage and respond to the increasing demand for faster network speeds and bandwidth. 5G speeds can be enjoyed by all Telemach users, as access to 5G networks is included in all bestselling VEČ mobile plans! Trusted by more than 620,000 satisfied customers, Telemach remains the fastest growing mobile provider in Slovenia focused on continuous upgrades and the provision of high-tech, high-quality and stable services.

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

We Can Adapt and Be an Active Partner

Anže Logar, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Slovenia.

editor

Jan Tomše

EXECUTIVE EDITOR AT THE ADRIATIC

What is important for the Western Balkans region now is the implementation of the Common Regional Market. If the Open Balkans initiative could give impetus to the implementation of the Common Regional Market, it would be good for the region, says Dr Anže Logar, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Slovenia.

With Anže Logar, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Slovenia, we talked about the achievements of Slovenia at the helm of the EU in the second half of 2021, today’s global challenges, and the Western Balkans’ opportunities and challenges in 2022 and beyond.

Slovenian presidency of the Council of the EU: which are the achievements the Slovenian diplomacy takes pride in, even though they might have occured outside media limelight?

The Slovenian Presidency of the Council of the EU is marked by dynamic developments in Europe and beyond. The uncertain epidemiological situation continues, and the world is facing several unexpected events – from the crises on the Belarus border and in Afghanistan, to new geostrategic alliances such as AUKUS – which called for a swift and determined reaction by the Presidency, all the while seeking consensus and demonstrating European unity.

Holding the Council Presidency entails complex legislative work as well as striking a balance between member states and the three European institutions – the Council of the EU, the European Commission and European Parliament.

At the outset of the Slovenian Presidency, we managed to seize the window of opportunity opened by the legislative procedure and a period of relatively limited spread of the pandemic, achieved progress in the long and tiring negotiations, which had not really been anticipated, and successfully completed the work on 20 legislative acts.

Furthermore, we stepped up the work on establishing the European Health Union that would facilitate member states’ dealing with transboundary health emergencies. We successfully concluded the negotiations on extending the mandate of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and the strengthening of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Another important achievement is the agreement among Member States on the European Health Emergency preparedness and Response Authority (HERA).

A major success of the Slovenian Presidency are the endorsements by the member states of the Digital Services Act and Digital Markets Act, which lay down new rules for a safer and more open digital space.

As the country holding the Council Presidency, Slovenia coordinated the EU’s mandate for participating in the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, where – together with the European Commission – it represented the EU in the negotiations with third countries. COP26 is an important step forward, keeping within reach the goal of the Paris Agreement to limit global warming to 1.5°C.

In foreign policy activities, I would like to point out the successful organisation of the EU-Western Balkans Summit on 6 October. It was attended by all the EU and Western Balkans leaders, who adopted the Brdo Declaration. It is particularly important that the EU reaffirmed its commitment to the enlargement process, and the Western Balkan partners reaffirmed their dedication to European values and principles and the need to implement the necessary reforms. The leaders also agreed to hold regular summits, with the next one to take place during the Czech Presidency.

We had invested a great deal of effort in the drafting of Council conclusions on enlargement and the stabilisation and association process, which were unanimously adopted by the General Affairs Council on 14 December and represent an important milestone in the process. Another notable achievement is the opening of Cluster 4 in Serbia’s EU accession negotiations (chapters on environment and climate change, energy, transport and Trans-European Networks).

Which are the main global challenges of today? More concretely, which are the main international challenges the EU is facing?

The world is facing challenges which were inconceivable only a decade ago: the COVID-19 pandemic, climate change, hybrid threats, cyberattacks, and new geopolitical divisions dictating that the existing multilateral system be upgraded with effective mechanisms. Another major challenge are the developments in the South China Sea; part of the attempts at addressing this issue is the EU’s Indo-Pacific Strategy. The occupation of Crimea continues, and the Russian Federation is massing military forces on the border with Ukraine, which is openly concerned for its safety. Other causes of concern include the rising energy prices and the question of strategic autonomy.

In multilateral forums, we can perceive growing polarisation between the democratic and non-democratic parts of the world; the concepts agreed decades ago and the “language” of the key rules governing the multilateral system are being eroded; new concepts undermine international frameworks and the human rights system. The instrumentalisation of international forums with various tactics, manoeuvres and procedures by the increasingly numerous and powerful autocratic regimes is causing further divisions and, consequently, undermines the efficiency and credibility of international organisations. The good news in this context is the US’s return to multilateral forums.

Slovenia is also striving to strengthen the EU’s common foreign and security policy and transatlantic relations, which is vital for resilience on both sides of the Atlantic and the best guarantee for enhancing the EU’s position.

How much international visibility and soft power has Slovenia built up? Where do you see Slovenia’s strong points, and which are the European strategic decisions that Slovenia, as a country, has a say in?

It is very simple: Slovenia has more clout now than a year and a half ago, and yet still not as much as it could have, given its international engagement, geostrategic position and state characteristics.

At the national level, we strive for reaching consensus when it comes to our fundamental foreign policy orientations. Therefore, during this mandate, we embarked on a review of our foreign policy strategy. After more than a year of intensive work within the Ministry and within the Strategic council of experts, we now have an updated document providing appropriate responses to contemporary challenges.

Slovenia is also striving to strengthen the EU’s common foreign and security policy and transatlantic relations, which is vital for resilience on both sides of the Atlantic and the best guarantee for enhancing the EU’s position.

In this regard, Slovenia endorses the strengthening of EU-NATO relations and of the EU’s resilience to hybrid threats, in the field of cybersecurity, military mobility, civil-military cooperation during crises and interoperability, as well as the institutionalisation of contacts between the two organisations. Resilience as a priority of the Slovenian Presidency enjoys wide support. In keeping with the Global strategy for the foreign and security policy of the European Union and the EU’s ambitions, Slovenia is actively involved in the process of drafting the Strategic Compass and is reaffirming its reputation as a credible, active and visible member state. The numerous successful Slovenian candidatures in international organisations in the last year are yet more proof that we are on the right track.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Slovenia has proved its solidarity with developing countries; since 2020, it has allocated a total of EUR 5.2 million to help them fight the coronavirus. With a total of over two million doses of COVID-19 vaccines donated, it is one of the largest donors per capita.

THE REGION

How stable a region is the Western Balkans at the moment? Regarding its European perspective, was there any meaningful progress achieved during Slovenia’s EU Council presidency?

The situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina causes concern, particularly the deepening political and institutional crises. We support the internal political dialogue and the constructive initiatives and debates focused on helping the country and encouraging progress on its path towards the EU, as this is in our common interest. We are resolute in our calls for ending the divisive rhetoric, establishing functional institutions and continuing the reform process. Slovenia supports the unity, sovereignty and territorial integrity of Bosnia and Herzegovina.

The normalisation of Serbia–Kosovo relations also remains a major regional issue. A comprehensive and legally binding agreement must be reached, and it must cover the entire spectrum of outstanding issues.

Stability and sustainable development of the Western Balkans are in our vital strategic interest as the region lies in our immediate neighbourhood.

In the final weeks of its EU Presidency, Slovenia has endeavoured to find a solution that would enable the launch of accession negotiations with North Macedonia and Albania. Along with the EU-Western Balkans Summit and the participation of Western Balkan partners in the debate on the future of Europe, the conclusions of the December GAC on enlargement raise hope for future enlargement steps.

When speaking of the Western Balkans, we cannot ignore the issue of succession. For Slovenia, the full implementation of the Agreement on Succession Issues is of vital importance as it implies respect for the rule of law in the context of fulfilling the assumed international obligations. Slovenia has repeatedly pointed this out, including at the European level, most recently at the EU-Western Balkans Summit.

Countries of the Western Balkans are actively pursuing tighter integration with the EU common market. How do you see the Open Balkans initiative, announced a few months ago, that currently includes three countries – Serbia, North Macedonia, and Albania?

To boost the economic development of these countries, it is imperative that we strengthen connectivity between the EU and the region in transport, energy, digitalisation, sustainable development, environmental issues and green technologies.

In October 2020, the European Commission published the Economic and Investment Plan for the Western Balkans, which includes €9 billion from the pre-accession instrument. In addition, the Western Balkans countries will be given access to the Guarantee Facility and the European Fund for Sustainable Development Plus, which will enable them the opportunity to take out favourable loans. A nice detail I would like to mention – in my capacity as Slovenia’s high representative for relations between the Council and the European Parliament during the Slovenian Presidency of the Council of the EU, I joined President of the European Parliament David Sassoli in signing the agreement that enables the drawdown of these funds.

What is important for the region now is the implementation of the Common Regional Market (CRM). If the Open Balkans initiative could give impetus to the implementation of the CRM, it would be good for the region.

There are many areas where this kind of cooperation could accelerate the region’s inclusion in European business flows, among them regional trade, investment cooperation, digitalisation to include the Western Balkans in the European digital single market and regional cooperation in industry and innovation.

All this would bring tangible benefits for the business world and citizens of the Western Balkan countries as they advance on their European path.

What is the security situation in the region? How can Slovenia, which is both a EU member state and knows the region, contribute towards improving security in the region?

The Western Balkans are still faced with divisions and outstanding issues, the legacy of the traumatic experiences in the recent past, particularly during the dissolution of the SFRY. It is vital to achieve reconciliation, and improve neighbourly relations.

If this goal is to be met, the countries need economic development and discernible benefits for the people, brought about by the reforms that need to be implemented as part of their EU accession negotiations.

LOOKING INTO 2022

How successful has Slovenia been in taking advantage of its geopolitical potential as a centrally located EU country, and a bridge between the stable Western Europe and the less stable East?

The division into a stable West versus an unstable East sounds like a cliché. If you look at the political situation in the countries in the East of the EU, you can see that their governments are usually stable and their political agendas concrete. They also experience high economic growth. Nonetheless, the unification euphoria we witnessed after the fall of the Berlin Fall has faded, some unfulfilled promises and expectations have led to disappointments that have cooled relations, and the economic and health crises have further worsened the situation.

In my opinion, Slovenia’s advantage lies in its agility; it can adapt to new situations and knows how to be an active partner. It was this realisation that encouraged us to update the strategic document of Slovenian foreign policy.

If the Open Balkan initiative could give impetus to the implementation of the CRM, it would be good for the region.

As Slovenia’s Minister of Foreign Affairs, where do you see the main challenges facing the Western Balkans as a region? How can economic diplomacy help?

Stability is a key challenge, particularly when it comes Bosnia and Herzegovina and normalisation of relations between Serbia and Kosovo. The continuation of the enlargement process with Albania and North Macedonia – in the package – is also of utmost importance. This is a most quickly achievable goal, a positive message the EU could convey to the region. Progress on these three issues would have a positive practical impact on improving the economic situation. However, it is also true that entrepreneurship, which is inherent to the people of Western Balkan countries, puts pressure on the political leadership to find solutions. And we should use this leverage to greater advantage.

Another important topic is the promotion of economic cooperation with the region. We know from our own experience the major role that international trade and foreign investments play in the transformation of countries in transition. At the end of 2020, Slovenian companies held €2.5 billion of investments in the Western Balkans, which is more than one third of all Slovenian outward investments.

From the standpoint of economic diplomacy, where are the biggest challenges, and opportunities, for Slovenian exporters seeking new market niches? We know that corporations have already started to shorten their supply chains, or put differently, to relocate production into geographically nearer countries with more stable business partnerships.

The answer is very simple: increasing added value, and achieving better positioning in supply chains. For this to be achieved, we need further investment in research and development. I see one of the opportunities in the EU recovery and resilience fund, which – with additional funds for a green and digital transformation – will give the Slovenian economy comparative advantages in the relatively large Western Balkan market.

Economic diplomacy has long been striving to bring Slovenian and foreign scientific or research institutes together, and connect them with innovative Slovenian companies with high added value.

In your opinion, which is the single biggest opportunity that Slovenian exporters still haven’t taken advantage of?

This depends on the market they want to export to. The European market is subject to market competition rules – the better they perform, the more they invest in the international network of contacts, and the more products with high added value they develop, the greater the chance of success. At the same time, it is worth considering some of the more closed or remote markets. This is where economic diplomacy can significantly contribute to strengthening bilateral trade. And that is why, during this mandate, we have intensified our activities in opening diplomatic missions and consular posts in the regions and continents where we had not previously been present, because such presence can play a significant part in entering into economic agreements.

Would you like to point to any outstanding goals you intend to fulfil during this mandate?

When I became Minister of Foreign Affairs back in March 2020, I set myself a very clear goal: to strengthen Slovenia’s activities in the European and international arenas. We at the Ministry have been working in this spirit for the past two years. Despite the challenging circumstances related to the COVID-19 pandemic, I participated in all major international forums in person or virtually, we carried out 61 bilateral visits abroad, and welcomed 43 foreign ministers and high-level guests to Slovenia. As I have already mentioned, we set up an informal C5 group, were invited to join the EU Med Group (formerly MED7) following extensive diplomatic efforts, established a permanent dialogue with Italy and Croatia on the management of the Adriatic Sea, relaunched and significantly strengthened transatlantic relations, established a strategic dialogue with the US, and carried out the Presidency of the Council of the EU. We also opened 3 new embassies (Dublin, Seoul and Riga) and a consulate in Milan to improve the representation of Slovenia abroad. All in less than two years. This is what we call “active diplomacy”. Diplomacy that does not limit itself. I am proud of our diplomacy because it has put Slovenia back on the map of countries that can make a difference at the international level.

Are we going to stop here? Certainly not. In 2022, we will continue to expand our diplomatic network by opening at least one more embassy. We have also decided to present a candidature for a non-permanent seat on the UN Security Council for the 2024–2025 term. We will continue to engage in active diplomacy and make effective use of the resources we set up for the Presidency of the Council project. We are not only strengthening our presence within the UN system, but also our dialogue with all of the key global players, including the countries that are particularly important for the Republic of Slovenia and its foreign policy and economic interests. I therefore see no reason to stop!

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

A Plot of Your Own

Local food

editor

Špela Bizjak

JOURNALIST AT THE ADRIATIC

Food self-sufficiency matters for the development of regions and countries. Organically-grown food has become a privilege.

Self-sufficiency can be considered a part of our daily routine, and a step towards a better life – one in which we take full responsibility for what we do. Moreover, self-sufficiency can bring us joy in our own productivity. Our farming ancestors ate what they could produce. Looking back in history, people were self-sufficient in water, food, and energy. Those who were not became extinct. So, it appears there still exists a very strong link between self-sufficiency and survival, despite all the opportunities created by global trade.

With an ever-faster pace of life, we demand to have everything at our fingertips, including – it goes without saying – fresh fruits and vegetables on supermarket shelves. At a time of COVID-19, everybody is thinking about people they care about. These should also include all those farmers who actually grow the food that lands on our plate, and all those involved in food processing and supply chains.

Farmers’ and bourgeois cuisine

While Slovenian towns were early hubs of trade and well-stocked with varied provisions, in the countryside, they only ate what they produced themselves. They cooked and baked on open fireplaces or in bread ovens. Cereals (wheat, millet, oats, rye, buckwheat, and, later, corn) served as staple foods. Cabbage and turnips were the most common crops while lentils and beans were the least.

Meat consumption in Slovenia decreased significantly in the 18th century. Potatoes began to be cultivated in the middle of the 19th century (after the great hunger of the 18th and 19th centuries). As for the rural population, their daily diet was a repetitive pattern weaved out of porridge, bread, milk, cabbage, and turnips. It was different during holidays, though, when they would eat stronger dishes seasoned with cured pork, and other delicacies enjoyed to this day. The oldest known recipes for a Slovenian dish are from 1589, from the court kitchen of Charles II. Apparently, the emperor was fond of the Carniolan cheese soup and of Carniolan štruklji with tarragon filling.

Food without packaging waste

Normally, there was no food-related waste in history. Townsfolk usually went shopping on the local marketplace with a wicker basket and carried canvas bags on them. But in the countryside, they had much less time for food preparation than in the city. On farms, housewives often had to join in working the fields, especially in summer, which is one of the main reasons why bourgeois and peasant menus were so different. Farmers served better meals only when they wanted to show off hospitality in front of guest.

The oldest known recipes for a Slovenian dish are from 1589, from the court kitchen of Charles II. Apparently, the emperor was fond of the Carniolan cheese soup and of Carniolan štruklji with tarragon filling.

The rising importance of local food

Even though many local traditions of self-sufficiency appear to be waning in today’s food production, a few cases to the contrary deserve to be emphasised. Say, Mercator, one of the region’s most important retailers of fast-moving consumer goods. Mercator’s primary mission has always been to offer consumers what they wanted and needed. Most customers want local offerings, home-made products that they know and trust. Locally made food has an important place in Mercator. This is why the retailer also encourages smaller producers and family farms to develop products with high added-value for customers.

Initial cooperation with smaller suppliers was so successful that Mercator has recently added another 60 products to an existing offering of 1,400 under the umbrella brand Radi imamo domače (“We love the local”). The product lines covers everything from milk and dairy products, meat, home-made juices and syrups, sweet snacks, mill products, jams, and honey, and is available on the shelves of more than 250 Mercator stores across Slovenia.

With a diverse and reliable offering of Radi imamo domače products, Mercator wants to increase both the standing of the joint brand and the position of smaller manufacturers. Above all, they want to reach even more customers who prefer to buy local.

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

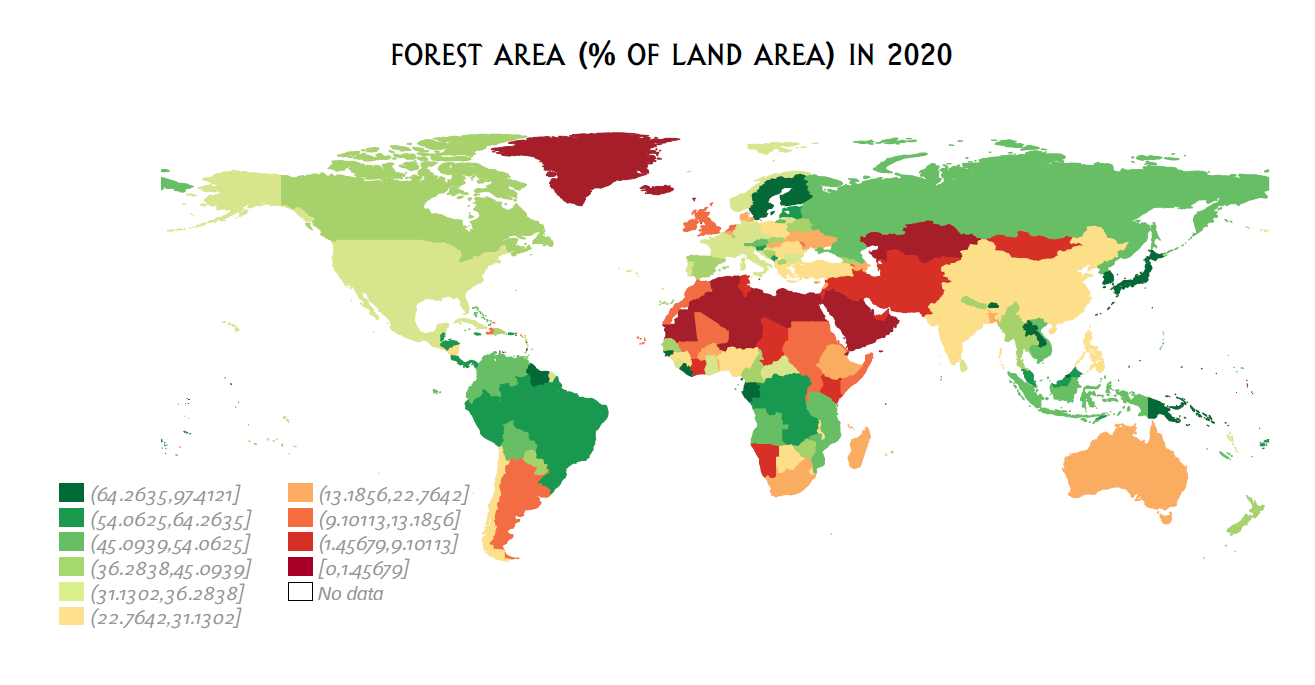

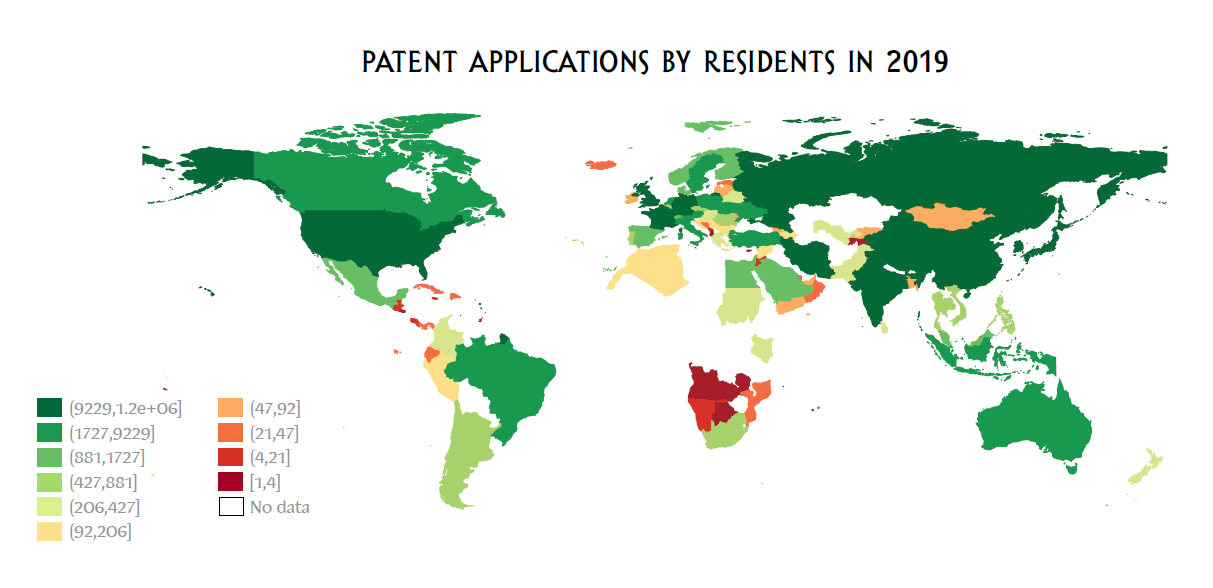

The World in Four Maps

Health and stress

editor

Jure Stojan, DPhil

ASSOCIATE EDITOR

“What we do see depends mainly on what we look for. ... In the same field the farmer will notice the crop, the geologists the fossils, botanists the flowers, artists the colouring, sportsmen the cover for the game. Though we may all look at the same things, it does not all follow that we should see them.”

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

Energy Fit for the Future

Challenges for the economy in light of the green transition

editor

Adriatic team

Institute for strategic solutions is organizing a discussion event on current issues related to the green energy transition: presentation of views and discussion by key stakeholders on current economic issues in the implementation of the green energy transition.

The purpose of the event is to present a view of Slovenia’s energy challenges, especially in the field of green energy transition in the economy. The fact is that after the corona crisis the European economy is moving towards a green energy transition. Companies will have to adapt their business models to this, because regulations and at activities at all other levels are focused on assessing whether companies are energy fit for the future.

The event will be held in House of the EU in Ljubljana, on February 15, 2022 at 10 AM.

Online registrations are required HERE

We have also enabled you to follow the event live online down below. Tune in on Tuesday, February 15.

Course of the event

10:00 – 10:05

Greetings from the host:

Jerneja Jug Jerše, Head of the Representation of the European Commission in Slovenia

10:05 – 10:25

Introductory speeches:

o Representative of the Ministry of Infrastructure of the Republic of Slovenia: Blaž Košorok, State Secretary

o Representative of the European Commission: Robert Kaukewitsch, Team Leader in the Renewables and Energy System Integration Policies

o Representative of EBRD: Vincent Duijnhouwer, GECA Associate Director

10:25 – 11:10

Presentations of invited speakers:

o Petrol representative: Jože Bajuk, Member of the Management Board

o SIJ Acroni representative: Branko Žerdoner, General Manager

o SSH representative: Dejan Božič, expert director for energetics

11:10 – 12:00

A discussion table with all speakers moderated by Tine Kračun, Director of Institute for Strategic Solutions

A few Tips and Tricks from Slovenian Executives

How to navigate in 2022

editor

Jan Tomše

EXECUTIVE EDITOR AT THE ADRIATIC

According to projections, 2022 will be a demanding and turbulent business year. In the shadow of the economic growth and inflation uncertainties, the managers will have to decide wisely about the supply chain challenges, lie in wait for the most suitable talents they want to attract, and try to reimagine their business models. Not to mention the challenges that may emerge from the tighter access to funds should the central banks decide to impose stricter monetary policy.

We asked some of Slovenia’s top managers what should managers focus on in 2022 in order to effectively lead their teams and tackle the challenges in the rapidly-changing business environment.

Closely monitor the key areas. Closely monitor the business, decision-making and the social environment to understand the changes and risks and develop various scenarios for the future of your business.

Manage your costs and take care of your supply chains. Control the prices of raw materials and energy sources. Establish secure and reliable supply routes.

Invest even more in digitalization and automation. As these investments may seem incosistent with the premise of cost control, you will capitalize on them in the long term.

Make your business a pleasant place to be. Build work environment that encourages creativity, good relationships, and flexibility.

Be open-minded, learn constantly. Develop preparedness for the jobs of the future. Promote life-long learning. In the fast-changing times and digitisation, work processes constantly change. The never-ending investing in new knowledge, skills and experience is the prerequisite for preparedness for the jobs of the future.

Feedback. Try to get it regularly, so you know where to focus your efforts.

Practice agility. The pandemic era sparked a stream of uncertainties, that demand adaptation and quick decision-making and imposing changes.

Delegate wisely. You can’t do everything yourself – show your employees that you trust them by delegating accordingly.

Exercise transparency. Encourage transparency of and in all processes. Be generous to understand each other’s situation and promote usage of kind words. Moreover, sharing positive quotes can help in a significant way.

Promote change.

At the organizational level. Empower your management and employees to be open to change which helps you adjust your business to the scenarios that will unfold.

At the personal level. Take care of your emotional well-being and joy of life.

Focus on motivating people. People are the most challenging part of the business. Work on retaining the existing talents and onboarding the new ones. Motivate them properly, develop seperate motivation strategies for each one of them.

Encourage solidarity within the team. Solidarity should not be a stranger to business environment. Nurture relationships within the team. Give feedback, celebrate wins. If you criticize, focus on the work, not the person.

We would like to thank the Slovenian managers who contributed to this advice:

Petra Juvančič, Executive Director, Združenje Manager – Managers’ Association of Slovenia

Gorazd Čibej, Managing Director, Insurance Supervision Agency

Karmen Dietner, President of the Management Board, Poklojninska družba A, d.d. Nada Drobne Popovič, President of the Management Board, Petrol d. d.

Andrej Lasič, Executive Director, NLB d. d.

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022.

If you want a copy of our annual magazine, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

Is the Open Balkan Initiative Light at the End of the Tunnel?

Strategic Foresight

editor

Faris Kočan, PhD

JOURNALIST AT THE ADRIATIC

In 2003, the idea of the European integration of the Western Balkans (WB) became the predominant political framework for managing the relations between the European Union (EU) and WB countries. 18 years later, this process is uncertain at least, while the region suffered “collateral damage” from a number of European internal crises (e.g. Ukrainian crisis, Refugee crisis, Brexit) which have prevented the EU to act more decisively and with a common voice.

In the last two years, the EU has adopted several documents1 that signal the preparedness to meaningfully engage with the region. However, recent developments such as the Bulgaria’s veto to North Macedonia’s EU accession talks amidst North Macedonia’s ”rocky road” towards fulfilling the enlargement requirements, has again raised questions regarding the future of the EU enlargement process. One thing is sure – the economic part of the cooperation is alive and kicking. The Economic and Investment Plan for the WB, which will generate up to €9 billion in the next six years, is something that the WB countries could use to enhance their own regional (economic) integration.

The most important domestic initiative is Open Balkan, a proposed economic and political zone consisting of Albania, North Macedonia and Serbia. Coming into force on 1 January 2023, the participating countries will open their national borders to each other’s citizens and products. The zone, which is mirroring the founding principles of the EU, should provide a platform for the eventual integration of the WB into the EU common market. If successful, it could provide a growth impetus for the whole region. This, in turn, would push regional relations towards more institutionalisation, and offer an opportunity for consolidating bilateral relations. Good neighbourly relations are widely seen as a precondition for a genuine transformation of a region still haunted by the memories of the worn-torn 1990s.

Slovenia: Just like in the year before, the general Investment Environment will remain moderately stable. The biggest risks to the general Investment Environment assessment are posed by public debt, tottering healthcare system, uncertain tax reform, accelerating inflation as well as property prices. The political environment is set to improve with general elections in spring 2022. It is widely hoped the contest yield the strong majority needed for passing socio-economic reforms.

Croatia: The Investment Environment in Croatia is improving, reaching the moderately stable mark due to the recovery measures and the stimulative economic climate put in place after COVID-19 crisis. In 2022, Croatia’s economy is forecast to further expand by 4.2%, continuing a strong economic recovery in 2021 (8%). At the Institute for Strategic Solutions, we will closely follow the announced tax reforms, which have the potential to stimulate domestic consumption and ease existing corporate tax burden.

Serbia: Coupled with robust investment growth, better economic indicators are driving overall improvement in Serbia’s Investment Environment, which can now be described as moderately stable. This is coupled by the country’s deficit reducing and improving debt-to-gross domestic product ratio, alongside the demand-boosting rise in pensions and salaries in the public sector. But the bright outlook could be marred by uncertainties regarding the bilateral relations with Kosovo, which is something to watch closely.

Bosnia and Herzegovina: At the Institute for Strategic Solutions, we estimate that the general Investment Environment is going to stay moderately uncertain. The political indicators will remain highly unstable due to the continuing non-cooperation on the state level. The situation could further deteriorate with the upcoming general elections scheduled for October 2022. This in turn could ‘lock in’ the current political crisis and intensify both the political and socio-economic risks until late 2022.

Kosovo: Kosovo is remaining moderately uncertain, mostly due to bigger socioeconomic and political risks. Such risks are associated with an anaemic economic recovery after COVID-19 crisis and the bilateral crisis with Serbia, which prevents meaningful dialogue between Pristina and Belgrade. Since this has a direct bearing on the ‘Open Balkan’ initiative, it should be watched closely.

North Macedonia: The Investment Environment is going to stay moderately uncertain amid the deteriorating political and security situation. Increasingly, social unrest has displayed both internal and external drivers; while internal dynamics have been triggered by the “fall” of Zoran Zaev, the external factors are inherently tied to ongoing bilateral tensions between North Macedonia and Bulgaria vis-á-vis EU integration. But it is the internal drivers which are the most worrisome for their spill-over potential. Indeed, they could determine the socio-political environment of North Macedonia in 2022.

Montenegro: While the Montenegrin Investment Environment is going to stay moderately uncertain, political indicators are deteriorating across the board. The political, religious and security situation remains tense after the 2021 violent protests in Cetinje. Concerningly, the political elites are fanning public discontent with hate-mongering statements. While such atmosphere is not expected to de-escalate completely in 2022, it is worth mentioning that the favourable Investment Environment is driving a general improvement in the country’s socio-economic situation. With 8.4-% economic growth, Montenegro is becoming a frontrunner in the region.

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

The Western Balkans Can Create Global Champions, but Only if We Work Together

Economic Integration of Western Balkans

editor

The Adriatic team

The Adriatic team

The Institute for Strategic Solutions (ISR), in cooperation with the Serbian Chamber of Commerce, organized a conference titled Economic Integration of Western Balkans. At the event, leading businessmen from Serbia and Slovenia reflected on opportunities and challenges offered by closer collaboration in the Western Balkans, with an emphasis on cooperating practices between Slovenia and Serbia. They emphasized the importance of swift economic integration of the region into the European Union. There should be no doubt: this integration is the only way for the region to make a breakthrough and prosper. At the same time, the Western Balkans have a challenge to position itself as a single, 20 million people market, which can provide the region with a better starting point on other markets, agreed representatives of some of the largest regional companies, including NLB’s CEO Blaž Brodnjak, President of the Management Board of Petrol Nada Drobne Popović, General Manager of MK Group Mihailo Janković and General Manager of Nektar Group Nenad Miščević.

“I believe we need to create regional champions. What will we offer to our children in a region of 20 million people to keep them from going elsewhere? How are we going to keep them here?” were questions raised by Blaž Brodnjak. He added that bringing together leaders in the region is the key to establishing a Scandinavian model of cooperation, which he sees as very appropriate for the region. According to Dragan Marković, CEO of Triglav osiguranje Srbija, the better infrastructure is needed for closer integration of the Western Balkans into the European space that will attract foreign investment, as well as digitalisation and automation. He is convinced that the region must support this with appropriate educational programs.

Tine Kračun, the Director of ISR, said that Serbian companies have recently been among the largest investors in Slovenia, which shows that economic and other cooperation between the two countries is strengthening. “But there is a border between us. This is the EU border. It makes economic cooperation and logistics difficult. Regional cooperation can only be fully realised if the routes are modern and the borders are open for integration and trade.”

According to Mihailo Vesović, the Director of the Serbian Chamber of Commerce, the results of cooperation between Serbia and Slovenia in the past 10 years are visible. He emphasized the importance of working efforts for even closer mutual integration. “It is crucial that measures are taken to remove obstacles for even closer cooperation. The goal is to create free economic space on the model of, for example, European Free Trade Association (EFTA), which removes obstacles for cooperation between European countries.” He sees another advantage of closer integration of the region in the joint appearances of companies from Serbia and Slovenia in foreign markets, for example in Africa.

Blaž Brodnjak, President of the NLB Management Board, believes that the current generation of businessmen should not only have the desire but also the responsibility to connect the region more closely. “We need to create regional champions. What will we offer our children in a region of 20 million to keep them from going elsewhere? How are we going to keep them here? An important answer to this challenge is smart specialization,” is convinced Brodnjak. He added that bringing together leaders in the region, both from business as well as politics, is the key to establishing a Scandinavian model of cooperation, which he sees as very appropriate for the region.

Nada Drobne Popović, President of the Management Board of Petrol, is convinced that integration in the region cannot be fully realized if companies don’t perceive themselves as regional players. Petrol walks this talk. “We wish to invest in the potential in energy sector. We are strongly present in Slovenia and Croatia. In Serbia, we see great potential for additional growth in gas, hydrogen and investments in renewable resources,” she said. The President of the Management Board of on of the largest oil companies in the region also highlighted the personnel aspect of operating as a regional company: “We already have more employees outside Slovenia than in Slovenia, although we generate half of revenue in Slovenia. To be able to carry out the processes from home, we digitalised ourselves in 24 hours during the corona period. After the end of the corona crisis, we used this know-how to improve our processes. I believe that other countries are pleasant to live in, and we as a company must ensure adequate pay so that the workforce stays in the region,” said Nada Drobne Popović in a conversation moderated by Nikola Papak, representative of the Serbian Chamber of Commerce in Slovenia.

Every market in the region is relatively small, especially in relation to Europe, but if we perceive the region as one market, this changes, said Mihailo Janković, CEO of MK Group. “We depend on each other. It is not enough to recognize the region as a single space, we must act like it as well. Our company is present both in the EU and in the region. We are proving that not only EU companies are welcome in Slovenia, but also that Serbian companies can be a good employer,” said Janković, emphasizing the importance of closer political integration into the EU, which is extremely important for the Western Balkans. MG Group sees great potential in Slovenia, with more than 200 million euros that have been invested in it so far – and with an additional 300 million euros of investment planned.

Marija Desivojević Cvetković, Senior Vice President for Strategy and Development at Delta Holding, says that in the region, in addition to the visible, there are also invisible borders, those in our heads. “It is clear that the only real path for the region is in the EU. Until that happens, states must act on their own. They need to establish a market that takes advantage of the same customer habits that undoubtedly exist thanks to a common past. “The Open Balkans initiative is welcome, but this process must be monitored by someone else. This could be Brussels. This way, the region will also catch up faster with the pace and direction in which the whole world is moving, “said Marija Dešivojević Cvetković.

“The right way is for this area as well as businesses operating in the region is to simplify everything they do as much as possible. Organizational structures, processes and other procedures. Just like in sports, you have to be fast in business. ”According to Nenad Miščević, CEO of the Nektar Group, a global company that is also present in Slovenia with its ownership in Fructal. Companies today have one common challenge, and that is inflation; Nektar Group, which operates in the food industry is of course also faced by it. “We cannot pass on the higher costs entirely to consumers. The company must also look for internal optimization and reserves,” pointed out Miščević, adding that they want to position Fructal as a premium brand in the food and beverage industry in the future.

Dušan Miličević, CEO of Comtrade Group, put the characteristic of resourcefulness in the region at the center of his thoughts. “The creativity this space possesses and which is very pronounced, for example, in sports, should be better used in the economy.” He pointed out that Serbia is among the leaders in the world in terms of the share of companies using cloud IT solutions. Integration seems extremely important to him. “We have to look at the region as one space and adjust the processes and the way we operate,” said Miličević.

Dragan Marković, CEO of Triglav osiguranje Srbija, presented his views on the integration of the Western Balkans from the point of the insurance industry. According to him, the first condition for closer integration is an even better infrastructure that will attract foreign investment. Marković also mentioned sustainable strategy and digitalisation as well as automation as important pillars. The region must promote these verticals through educational programs that adequately support the goals. “The insurance industry is an integral part of economic development. We must be prepared for the enlargement of the EU as best as we can be. During the corona crisis, it became clear that this region could help others as well. Serbia, for example, has donated the necessary vaccines to other countries.”

Slobodan Šešum, Acting Director-General of the Directorate for Economic and Public Diplomacy at the Slovenian Foreign Ministry, emphasized the importance of the region’s enlargement and integration into the EU to happen fast. It is the main export market for both Slovenia and Serbia. That is why it is important to remove the borders that hinder economic cooperation as soon as possible, is convinced Šešum, adding that a quarter of Slovenian companies plan to invest in Serbia and Croatia as well as in other countries in the region.

NLB Makes a New Contribution to the Region’s Integration

Building a resilient economy

editor

THE ADRIATIC STAFF

NLB connects South East Europe as one of the region's leading banking houses, and now it has added sports to the mix. NLB has become a sponsor of the ABA Basketball League. "We have found a regional partner in the league and the opportunity to confirm our commitment to the development of the region with this sponsorship. Basketball is the team sport that has written the most resonant and inspiring stories in the region," NLB comments on the newly-established partnership.

The NLB Group is joining the ABA League in the 2021/22 season and the cooperation between the two regional players, who are both leaders in sports and banking and financial sector will continue until at least 2025.

By entering this region’s most powerful basketball competition as a sponsor, the NLB Group has also become the general sponsor of the second division competition under the auspices of the ABA League which will from now on be called NLB ABA LEAGUE 2.

“We are more than just another financial group and as an institution of systemic importance we are not only interested in business topics exclusively. We want to create, enhance and connect the region of opportunities operated by the Group in various ways – also through sports. Basketball is a team sport that has written the most popular and inspiring stories in the region, telling us about winning and success, both with the national team and basketball clubs. By sponsoring the ABA League j.t.d., the NLB Group has proved once again that it knows the passion and desires of the region of opportunities, and that it speaks the same language and culture. Consequently, our Group understands and promotes what people in this region cherish. We are members of the same team. And the teamwork, bringing different communities, cultures and languages together to form a rock-solid whole, which is able to seize every opportunity through coordinated action, are the very values of the NLB Group,” said Blaž Brodnjak, CEO of the NLB.

Dubravko Kmetović, director of the ABA League: “On behalf of the ABA League j.t.d., I am happy and honoured to welcome (back) the NLB Group to our joint home of basketball. The NLB Group was with the ABA League j.t.d. at the very beginning, when this whole idea of a regional basketball league came to life, and I am extremely happy to have this renowned banking and financial group again by our side.

THE ADRIATIC

This article is part of The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022 project.

If you want a copy of our annual magazine, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.

When It Comes to Esg, the Sooner, the Better

Interview: Bogdan Gecić, the founding partner at Gecić Law

editor

Barbara Matijašič

JOURNALIST AT THE ADRIATIC

Environmental, social and governance (ESG) preparedness will have a pivotal impact on the future financing of businesses as well as on their cost of operations and legal compliance. Belgrade-based Gecić Law is the first independent law firm in the region to provide services in the field of ESG.

Gecić Law is a prominent regional law firm that helps clients navigate through the complex legal landscape of the region across multiple practice areas. It is especially known for its expertise in EU law and international trade. As countries of the region open new chapters in their EU accession talks, Gecić Law relies on its creativity and in-depth knowledge of both legal and key business issues when providing innovative and practical solutions in the most complex of matters. Gecić Law is the only regional law firm that has continuously represented clients in crucial matters before international institutions, including the European Commission, the Energy Community, the ECAA, and CEFTA.

We spoke to Bogdan Gecić, the founding partner at Gecić Law about the firm’s achievements and its strengths when advising diverse entities in the SEE region. He singled out innovation as the key ingredient to the firm’s success and the decision to expand into new practice areas such as ESG, one of the most pressing issues of our time. Gecić also shared his thoughts on how compliance with ESG demands may affect businesses and market dynamics in the region and beyond.

What are the main achievements you are proud of, and which are the key ingredients to the success of Gecić Law?

We are immensely proud of being named Law firm of the year: South Eastern Europe at The Lawyer European Awards 2021, in a new category encompassing a dynamic market of 150 million people, including Turkey and several EU members. This is not the first time we have been recognized by the preeminent judging panel, which includes experts from leading multinationals, such as Starbucks, GSK and Hugo Boss. Last year we were named Law firm of the year for Eastern Europe and the Balkans and we have repeatedly entered the European Competition or Antitrust Team of the Year – Top Five category, along with the most distinguished antitrust teams across Europe – for example together with Latham & Watkins, a team that represented Google. Our firm is also consistently recognized by elite global directories, including The Legal 500, Chambers and Partners and Benchmark Litigation.

The most important ingredient for our continued success is innovation, which is about continuous learning, discovery and adding value to our clients’ businesses. This leads us to expand into new practice areas, including ESG. We were the first independent law firm in the region to introduce services in this vital field. Forward-thinking global law firms, including Cleary Gottlieb, Clifford Chance and Linklaters have all understood the importance of ESG and we are glad to be in their company.

ESG is one of the most pressing issues of our time. How are the companies in the SEE region prepared for these changes? Can you point to the the winners of »the new era«?

Our clients usually know that they will have to face changes as part of the EU accession. However, they are not always abreast with how these changes may affect their businesses and what the dynamics may be. Another set of issues arise from trade with EU countries.

The Green Deal will bring several potentially ground-breaking challenges, including the carbon border tax, which may have far-reaching consequences for the regional economies. ESG preparedness will have a pivotal impact on future financing (e.g., Green Bonds) as well as on the cost of operations and legal compliance. Companies may be forced to adjust their business models to remain competitive. We provide holistic assistance and help clients incorporate ESG into their overall business strategies. Those who understand this well and act quickly will be the winners of the new era.

So how can law firms assist their clients during their transitions to ESG practicum? Does this support differ from market to market? How?

Our experience shows that most markets in the region face similar challenges with ESG. As we saw in Denmark, acting on climate change could increasingly become mandatory. Regional markets moving through the EU accession process may also have to comply with the new rules soon. As the ESG movement gains momentum, we aim to provide solutions tailored to the specific goals and needs of each business. We first assess and analyse the risks a client may be exposed to and then advise on how to best adapt, from a regulatory, strategic, financial and operational standpoint. In the implementation, we prioritize between the“must-have”and the“nice-to-have” but we do provide a clear roadmap for each area.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

Gecić Law aims to provide solutions that are tailored to the specific needs of each business: first by assessing and analysing the risks a client may be exposed to, and then by advising on how to best adapt – from a regulatory, strategic, financial and operational standpoint.

The sooner, the better. Some businesses still do not realize that failing to prepare may significantly affect their ability to compete in the market, sell their products and have access to financing.

Those who understand this well and act quickly will be the winners of the new era.

What are the key market challenges in ESG in the SEE? Can you specify the most important for the year ahead and how will you address them?

Many businesses have a short-term approach, seeing change as an additional cost, avoiding and postponing action. Some still do not realize that failing to prepare may significantly affect their ability to compete in the market, sell their products and have access to financing. Regulators, investors, creditors, customers, and other key stakeholders will insist more and more on responsible business conduct. We advise clients on EU rules on ESG that will define international trade in the years to come, impacting exporters and entire supply chains in the Western Balkans and beyond.

Nevertheless, our region is also showing remarkable progress, as major cities, including Belgrade, expand their supporting infrastructure to accommodate the latest environmental trends in personal mobility, waste management and renewable energy supply.

Last but not least – how does your own firm approach ESG practices?

We are thrilled to be part of this process, as we also take on board ESG standards. Wouldn’t it be completely inauthentic if we did not adhere to what we preach? We incorporate these principles into our core values and our everyday work. Our active and collaborative approach to making a positive contribution is reflected in our work with the Responsible Business Forum.

We are also a founder and proud supporter of the annual Taboroši Scholarship. We stand for an inclusive and diverse working environment, as we strongly believe that different perspectives and experiences enrich our business in a meaningful way.

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.