Trains, the Environment and the Future

Trains are the past and the future

Martin Pogačar, PhD

SPECIAL CONTRIBUTOR

Today trains are often seen as a means to alleviate the burden of travel on the environment. The worst culprits are flying and driving.

The primary motive may not always be related to environmental awareness but is rather pragmatic i.e trains mean shorter travelling time and less security control hassle. A journey from Munich to Berlin, for example, can take about four hours, during which time you can work, read or simply relax. However, travelling from Ljubljana to Nova Gorica, or abroad to Berlin, Vienna, or Budapest, is still a day-long adventure – or such is the popular myth!

Intercity train connectivity is indicative of not only geographical factors, but also economic and political decisions, or in many cases – non-decisions. For example, in the early 21st century, Slovenia was notoriously badly connected by railways, both nationally and internationally, as well as on a state level. There still seems to be little political understanding or comprehension of the increasing significance of the railways and their effects on travel and the environment. There appears to be a total lack of awareness that trains are the real future of travel – much more so than futuristic flying cars are!

The railway system and trains have a colourful history, amply represented in popular culture. A look at railways as represented in Yugoslavian documentaries can give us some perspective on post-war reconstruction, as well as on the relationship between people and the environment. And not least, they can encourage us to think about the state of the railways in Slovenia today.

Railways first cut nad dug their way into Slovenia with the construction of the Vienna-Trieste line. The construction started in 1837 and the last leg was finished in 1857. It connected Vienna, the capital city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire with the port of Trieste, and was known as “The Southern line”. It grew to become a crucial link in the transport of goods and people alike. Over the decades, new branches connected people living in the vicinity of the railway with other parts of the empire; it also greatly facilitated trade and commerce and aided sprouting industries. The railway ignited imagination and travel on an unprecedented scale.

The machine, which Karl Marx described as the technical equivalent of revolution and gistorical progress when he said, “revolutions are the locomotives of history”. They harnessed the power of steam, fossil fuels and later, electricity. However, the railway also created ambiguity. Walter Benjamin (German Jewish Philosopher, 1892-1940) observed changes in the very composition of interpersonal relationships, stating that the railway represents “the first vehicle that creates and shapes the masses, whilst at the same time, a train ride allowed people to observe the faces of others close up, and in silence”. On the other hand, the historian, Wolfgang Schivelbusch, in The Railway Journey, emphasises the role of the train in the shifting human perceptions of the world which started in the 19th century and continues to this day. Ultimately, it was the railroad that contracted the world, caused the deaths of thousands in construction, and during WWII provided the lethal infrastructure for the industrial-scale mass murder perpetrated by the Nazis.

The train and the railway, the machine and the infrastructure thus epitomise the post-Enlightenment rationalisation, the march of science and the industrial revolution. They are a sign of progress and oppression, life and death, opportunity and destruction. The train represents a radical break in the ways people relate to each other and how they see and understand the world.

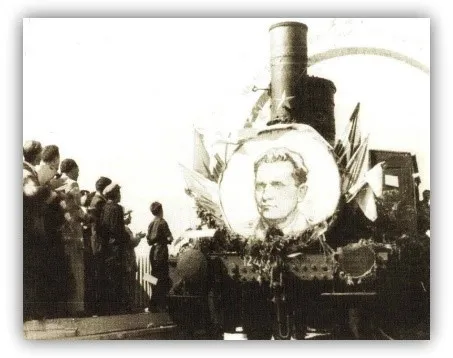

In this context, the Yugoslav post-war reconstruction may offer some insight into how the emerging socialist state, straddled between death and ruin in the aftermath of WWII, constructed the railways in 1945. It was seen as an industrial and symbolic part of the ideological push to not only reconstruct the country but also to create a future for the new socialist man. This is portrayed particularly well in newsreels and documentaries.

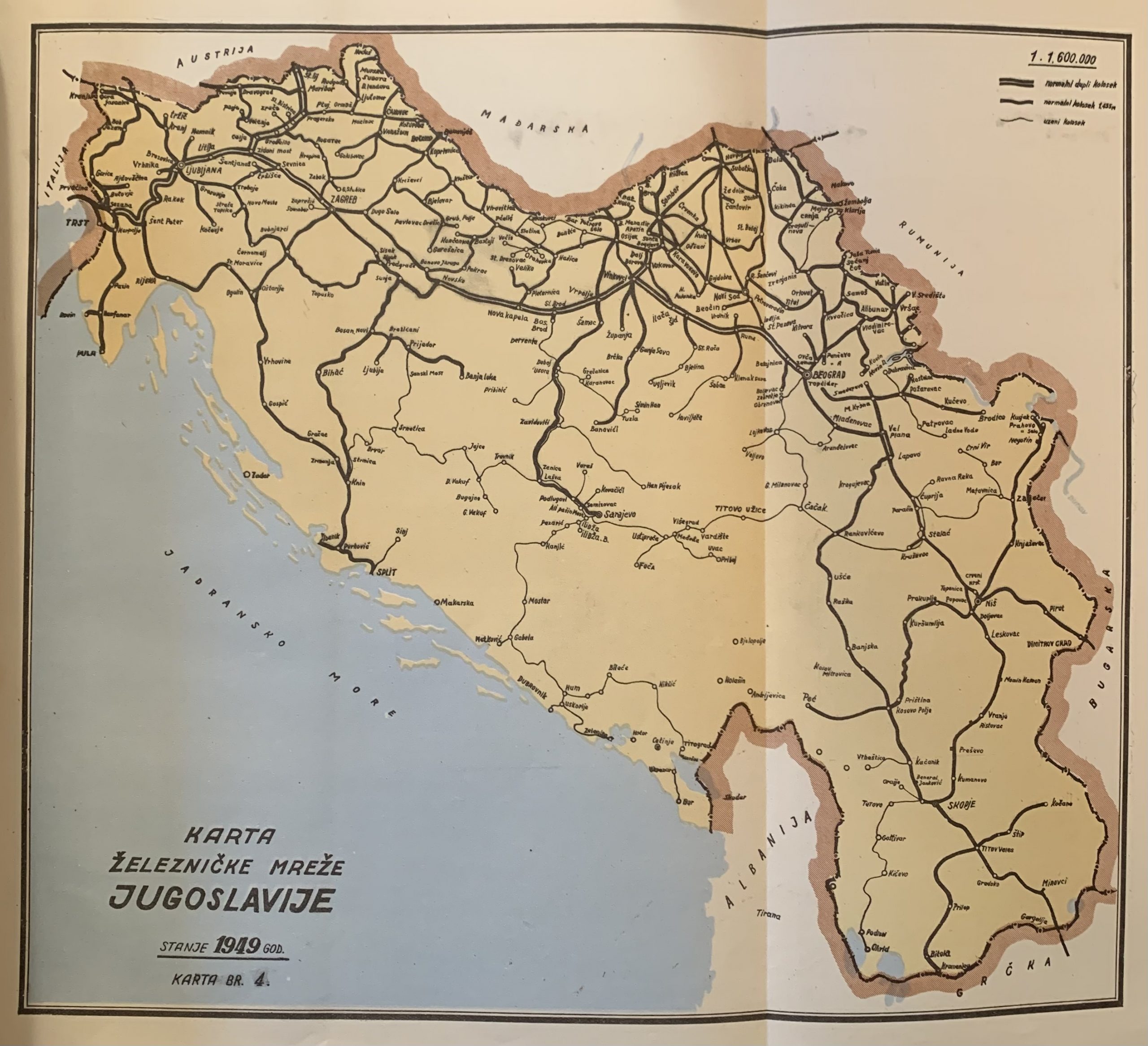

The 1972 documentary Diverzije na železničke objekte (Railway Object Sabotage, Zvonimir Saksida) presents some statistics about wartime railway infrastructure destruction. In the period 1941-1945, 1799 km of railroads, 830 railway stations, 2122 bridges, 90 tunnels, 1200 locomotives and 12,000 train cars were destroyed in the former Yugoslavia. This toll of destruction was caused by the occupation forces, resistance sabotage, and allied bombing, and was added to other infrastructural damage in a predominantly agrarian country. The human loss was enormous, nearly 600,000 people died, while, as in any war, the psychosocial damage to the survivors is much harder to measure. Before WWII, the former Yugoslavia was only sparsely industrialised.

In the immediate post-war years, socialist Yugoslavia ran a severely damaged railway infrastructure. It was grafted onto an inherited railway system which before the war was mostly concentrated in Slovenia, northern Croatia, Serbia and Vojvodina, with very few connections to Bosnia. This was the consequence of the fact that from early on up until World War II, the railway was attuned to the economic-political ambitions of the Austro-Hungarian (Slovenia, Croatia, parts of Bosnia) and the Ottoman Empires. Therefore, after the liberation in 1945, the new Yugoslavia was confronted not only with ravaged and almost non-existent railways but with an existing network more attuned to Vienna, Budapest or Istanbul as was noted by the Slovenian historian, Anton Melik.

In addition, the post-war situation was marked by large numbers of injured and traumatised people, who had emerged from the war without much formal education. However, this was to some extent alleviated by the fact that resistance units also had cultural sections that oversaw cultural activities as a critically important part of socialist ideology. This included theatre and poetry, as well as practical political and ideological education. E.P. Thompson, a British historian, took part in the international shock-worker (udarniks) brigades in 1947, namely the Šamac-Sarajevo construction site. He wrote the following in his edited volume The Railway: An Adventure in Construction.

A great part of the pre-war educated class had been killed in the war or had been discredited by collaboration with the enemy. Men of forty, fifty and over were performing miracles of self-education, but the bulk of the teachers, technicians and professional men of the future had to be found among the students and young workers of 1945. Some had walked out of their schools at the age of fifteen and gone to the forests, not to return for four or five years. Others had sment two or three years as prisoners in concentration or slave labour camps. The problems of psychological readjustment were considerable. Like many other Europeans, they had grown up in isolation from the cultural and intellectual life of other nations. Even the raw materials of education – the textbooks, libraries, instruments, schools and laboratories – were in short supply.

The ambition of the post-war socialist government was not only to (re)build the railways, but the infrastructure at large. The government also placed a great emphasis on the public education system and health care. These were seen as the conditions for the (re)construction of the material as well as the symbolic.

At this point, the railway became a more-than-material entity – a phenomenon that sublimated a wide variety of expectations and ambitions, dreams and an idea of the future. This was embedded in the brigade workers moto: “We build the railway, the railway builds us!” that connected the human with the future and the material with the symbolic. Implicity, it connected humans to nature through labour.

The railway construction work represented a radical intervention with nature, which, especially in a context of material scarcity and poor mechanisation, required a lot of manual labour with sub-optimal tools.

The workers had compressors and drilly, dynamite, wagons, and mining equipment. But most of the work took place without professional supervision and only the most primitive tools were used – bare hands, picks, axes, heavy wheelchairs with one wheel.

The 1947 film Omladinska pruga Šamac-Sarajevo (Sarajevo Youth Railway, Slobodan Jovičić) presents the results of months worth of the shock brigades work. The film focussed on the shock brigades who constructed the railway from the town of Šamac to Sarajevo in Bosnia. The film starts with maps and statistics: the length of the tracks, the number of construction workers (211,000 domestic and 4,000 foreign), the number of tunnels dug and bridges constructed, the amount of dirt moved (5,5 million metric tons) and concrete used (1.9 million metric tons). These are considerable numbers that in the modernist manner of keeping statistics tell of the human engagement with the earth and rock using sprades to dig and hands to tighten the screws.

The film narration describing the work is intercut with shots of waving flags, which is accompanied by ochestral music. Upon the arrival of the train to Sarajevo bringing in shock workers to a city flooded with people, the narrator states – “A new life is celebrated, a broad path to a happy future”.

These scenes are interspersed with the scenes of the train ride across the countryside. Here, nature is the background, the scenes include the tracks, the tunnels, the bridges, and the laying out of tracks into the future. It is also an actor that observes and gives way to the construction of the new march of progress to steam and steel. “Enabling fast and cheap transport, a wide gauge railway enabled the opening of new forest construction sites, where today a persistent struggle for high productivity ensues”, the voiceover explains.

This alludes to the imperialist approach to the construction of nature – only when nature is mastered can it be exploited. Thus, the whole (re)construction enterprise was inscribed into the processes of modernisation into the processes of modernisation and industrialisation in which the machine figured prominently as an extension of humans overcoming themselves. Yugoslavian writer, Ivo Andrić, wrote: “When these efforts of mature people and experts are joined by the already known work enthusiasm of the youth, the real struggle begins with the struggle against the forces of nature, the struggle with the mistakes of the past, and the struggle against prejudice”.

Thus, it was not only the railway that was constructed. Anthropologist, Andrea Matošević, notes, “The opposition [of man in nature] is realized by a radical change in nature that is reflected in two ways – as a significant transformation of its morphology, but also as gaining the experience necessary for active transformation, and thus creating the new socialist man”.

The narrator in the Memories from the Tracks, (Uspomene s pruge), Hajrudin Krvavec, 1952) documentary, explains this concept against shots of trains driving through the land, crossing bridges, workers pushing cartwheels and shovelling, shots of explosions and workers singing. He says in an uplifting tone. “Again, the explosions in the valley of Bosnia mark the beginning of the construction of a new youth railway. Again, the silence of the landscape will be pierced by the songs of youth”.

The relationship between nature and humans here is crucial in terms of recontruction, as it involves labour, one of the ideological tenets of socialist Yugoslavia as a country of the working people, with the main means of engaging with the land. In line with the workers motto, “We build the railway, the railway builds us”, it presupposes a struggle with nature, reframing it as a condition of human progress, which also defines the construction of the new society, as the author in a 1948 book Sto godina železnica Jugoslavije noted: “On this Youth railway, the alliance between our working class, the working peasantry and the intelligentsia was deepened and further strengthened”.

This is coupled with some Slovenian newsreels showing images of railway construction and students enrolling in courses at the Faculty of Medicine, indicating the value and the societal need for both, not least because health is a necessary condition for an efficient workforce. What is more, a newsreel from 1946 shows children reading, clearly delivering the message about the importance of education and literacy for the construction and reconstruction of society.

In a somewhat younger documentary in 1954 Ljudi i čelik (Humans and Steel, Slobodan Jovičić), the relationship between humans, technology, and nature is shown in a somewhat different manner. The film depicts the transformation of the Bosnian town of Zenica, from a small ironworks hamlet into an industrialised socialist city. “A street appears here, a new factory there,” says the narrator, “every day, the traces of the old disappear”. These words are spoken against shots of old, derelict houses and new modernist blocks of flats, with tall chimneys and factory halls rising in the background. We see workers casting iron in heat and hear the deafening noise of hammers pouding steel – “the steel heart of our homeland”.

We also see President Tito addressing the shock workers arriving in Sarajevo in 1947, “You have shown to the entire world that Yugoslavia is the land of peace, that it is hard-working, and it is constructing. But remember now it’s time to learn and then it will be time to work. You need to learn what will enable you tomorrow to even better serve your homeland”. The scenes of hard-working women and men are interspersed with shots of lakes and forests, of cities at night with people going to the cinema or theatre. The new socialist man must also rest. And the viewer is then taken back again to see the night shift at the steelworks. The urgency of post-war reconstruction had transformed into everyday rhythms of life in peace.

The documentaries reflect the drive to rebuild their war-torn homeland, which is in line with the modernist conception of progress that marked the post-war idea of a better future in both the soclaist east and capitalist west. It shows the very strong push to frame the human, nature and technology in the context of an ideology of reconstruction and progress. For a long while, Yugoslavian railroads also presented an infrastructure of brotherhood and unity and were the main transportation system that shifted goods and people across the land and beyond; and it remained so until the ideology of the car and individualised travel took over, resulting in disinvestment and the closing down of lines.

From today’s perspective, socialist Yugoslavia’s feat in construction unfolded in very specific geopolitical and historical conditions. They just might provide an idea that large-scale constructions, if their importance is acknowledged, do not need to take decades to construct. For at least 30 years it has been clear that the railway is the future of mass mobility, therefore it is all the more shocking that the state of Slovenia lacks any strategy on how to revive and improve its railway system and connect it beyond its borders. If the ride from Berlin to Munich takes just over four hours, why does the ride from Ljubljana to Nova Gorica take three?

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic Journal: Strategic Foresight 2023.

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.