Chocolat Lombart missed the mark on predicting future

The Future Used to Look Like This

Jure Stojan DPhil

ASSOCIATE EDITOR AT THE ADRIATIC

‘How will our great-grand-nephews live in the year 2012?’ This was the design brief that landed, in 1912, with the renowned Parisian art printers Norgeu.

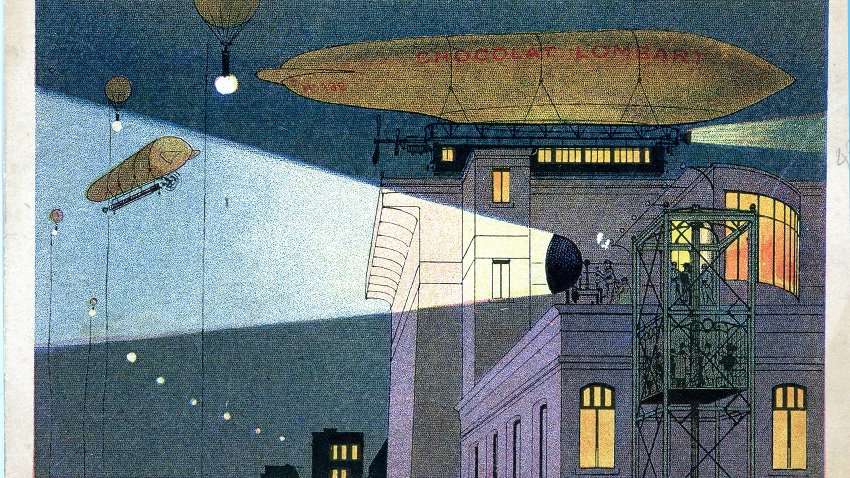

The client was the Parisian chocolate maker Lombart – at the time, chocolatiers competed not only on taste of their produce but also on the quality of collectible cards included with food packaging. This commission resulted in a set of six postcards that have since achieved anthological status in the history of advertising art – sometimes referred to as ‘chromo’ since it was printed in chromolithography, a technique invented in the 19th century. These postcards also feature in the classic reference work on the topic (mostly, a showcase of Bibliothèque Nationale’s collections) – Christophe Canto’s and Odile Faliu’s The History of the Future: Images of the 21st century (Paris, 1993).

Parallel worlds

The Chocolat Lombart cards depict an eery kind of parallel reality – what is supposed to be our contemporary life but evidently imagined in the waning years of the Belle Époque. They represent vintage steampunk, to use 21st-century keywords. All characters are dressed in the latest fashions of 1912 – an understandable artist’s choice. After all, fashion is supposed to be in touch with the future (at least this is what designers have argued for centuries). But it is not only the clothes and the grooming that make the images instantly dated (in both senses of the word). They reflect a rigid social world which is clearly structured and hierarchical. Servants bow to the whims and desires of the select few which literally hover above the masses. Ironically, these two aspects appear less anachronistic in 2021 than they did, say, in 1951 – a consequence of hipster fashion, both in apparel and facial hear, and of rising economic inequality.

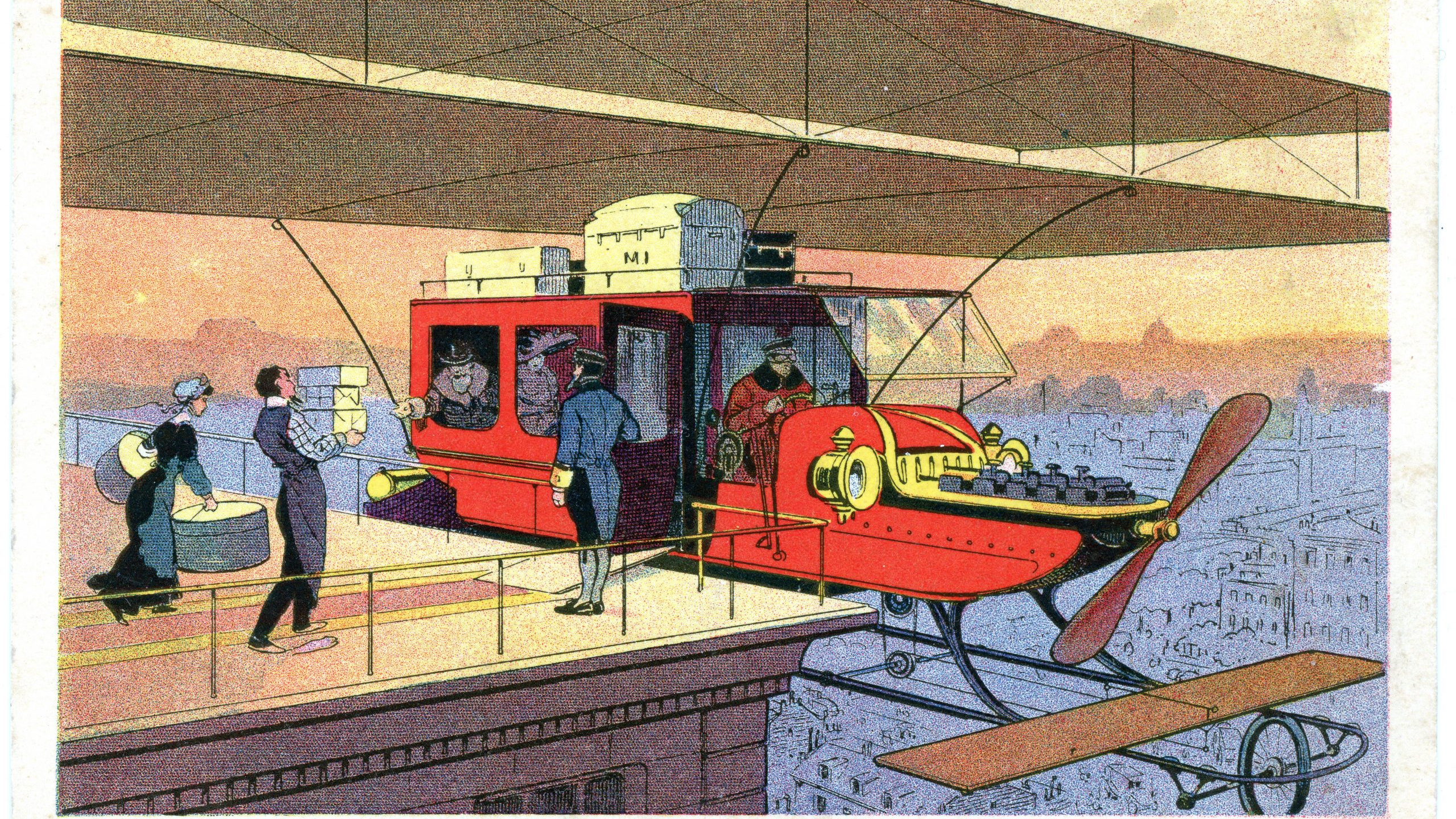

Another sure giveaway is the central deceit of these images – all of them imagine how in 2012, consumers are driven by an unstoppable urge to fetch Lombart chocolates. This is, of course, blatantly untrue. Unimaginable as it might have been in 1912, neither the brand nor the company survived to see the new millennium. They disappeared in 1957 (in this case, business longevity did not equate with immortality – Lombart had claimed to have been founded in 1760).

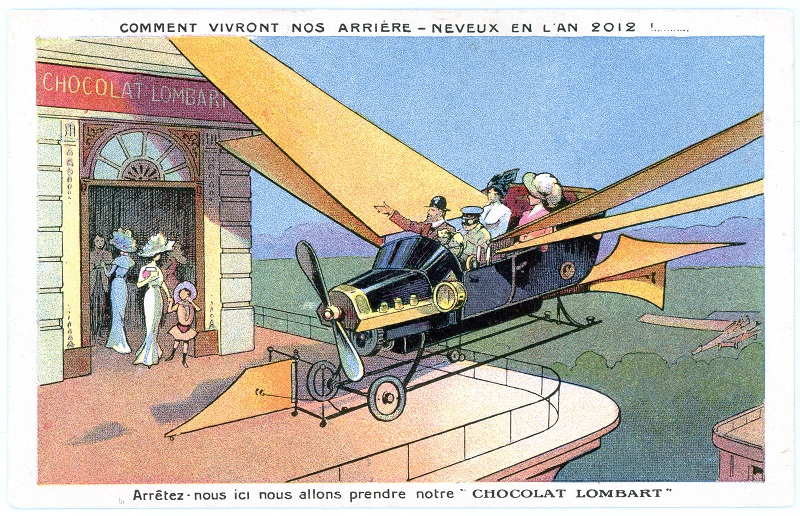

Such details aside, two out of six predictions proved to be remarkably prescient. We really did have video calls in 2012, even though only a minority would opt to use a video projector. There really are tourist submarines touring the seas, including in the Adriatic, even though they operate at much shallower depths than imagined in 1912 and do not dock to special under-water stations. Another prediction was a near-miss – while humanity did indeed make it to the Moon in 1969, there are still no regular civil flights between Earth and its natural satellite. And interplanetary rockets decidedly look very unlike the space car imagined in the name of Chocolat Lombart. The artist most obviously failed in the prediction apparently designed to flatter the client’s ego. It almost feels petty to point out that in 2012, there were no regular deliveries of Lombart chocolates, by zeppelin, from Paris to London.

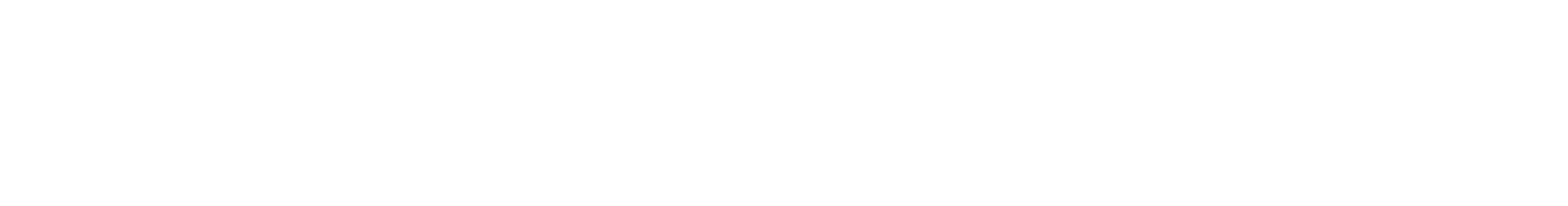

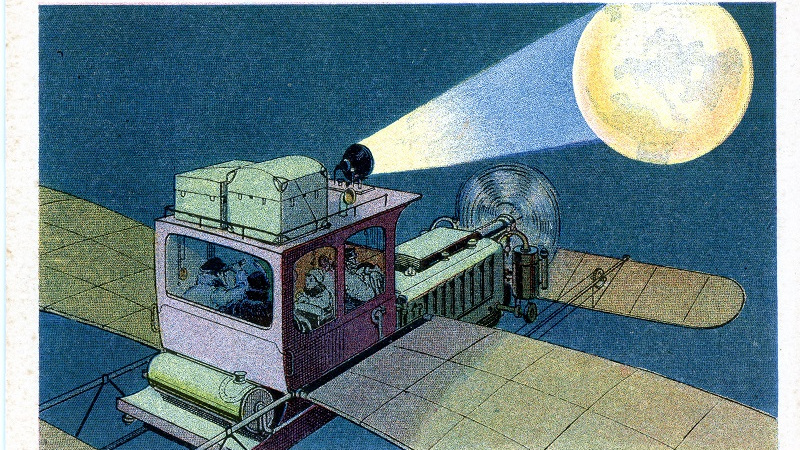

There was a prediction the artist was apparently most confident about – as implied by the fact that it is laid out over two cards. Namely, that of the flying car. Now, the flying car is a somewhat of an iconic object, existing in numerous plans, drawings, and science-fiction films and, even as working prototypes – but not (yet) in the lifestyle-defining way the artist envisioned.

To the late anthropologist David Graeber, the very absence of flying cars was damning evidence that capitalism had lost its mojo (he blamed all-pervasive bureaucratization). Incidentally, Graeber’s essay was published in 2012. But it should be noted that the flying cars he had in mind were those predicted for 2015 as recently as 1989 in the movie Back to the Future II. Many will be heartened to hear that in 2021, flying cars are once again being developed by several companies around the world.

Lessons of (failed) predictions

The futuristic prints distributed by Chocolat Lombart in 1912 are charming pieces of printed ephemera. But they are also vivid illustrations of what works – and what doesn’t – in future studies, technological predictions, and economic forecasting (the process of trying to guess the future carries many names depending on the field of study). It all follows from one central observation. Namely, that Chocolat Lombart’s year 2012 is merely a 1912 with fancy stuff attached to it.

First, while it makes sense to predict the short run by extrapolating from the most recent data points (say, the latest Paris fashions in coiffures), this yields extraordinarily twisted and distorted visions of the long run.

Second, even though the biases of extreme extrapolation may be easy to spot in its total effect (in aggregate) mere decades after the prediction was made, it is difficult to say which particular detail will turn out to be most off the mark. The sumptuous beards displayed in some images would have marked them as ridiculously out-of-date by the late 1930s. After the spread of hipster fashions of the 2010s, pre-World-War-I trends in facial hair and clothing no longer appear that anachronistic.

Third, predictions work best when consumer experience takes centre stage, and the forecaster imagines what invention could possibly bring further ease and comfort.

Fourth and last, even when making predictions about technology, leaving out the society seriously derails the forecast. Working at a time when the gap between the haves and the have-nots appeared unsurmountable, the artist could not imagine that 20-century airline industry would be based on mass mobility. Airbus’s A340-600 can carry up to 475 passengers in high-density seating. The cars imagined by Norgeu’s printers could carry at most six. One detail is especially telling – the driver of the flying limousine does not share the cabin with the exalted passengers but must freeze outside. This implies the chauffeur’s comfort was not considered part of technological progress, it was not something flying car makers were supposed to think about. (Ironically, even this appears less absurd in 2021 than it did as recently as in 2019 – having the passengers and drivers physically separate would greatly aid pandemic mobility).

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic Journal: Strategic Foresight 2021

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.