ISR gathers leaders on capital and competitiveness

Discussion surfaces tensions between Brussels frameworks and regional realities at Strategic Foresight event.

Andraž Tavčar

Outside the Ljubljana City Museum on Tuesday afternoon, snow fell steadily across the city centre, the kind of sustained winter weather the Slovenian capital hasn’t seen in years. Inside the museum’s intimate cinema-style conference space, roughly a hundred people brushed flakes from their coats, collected glasses of wine, and exchanged New Year’s greetings before settling into their seats.

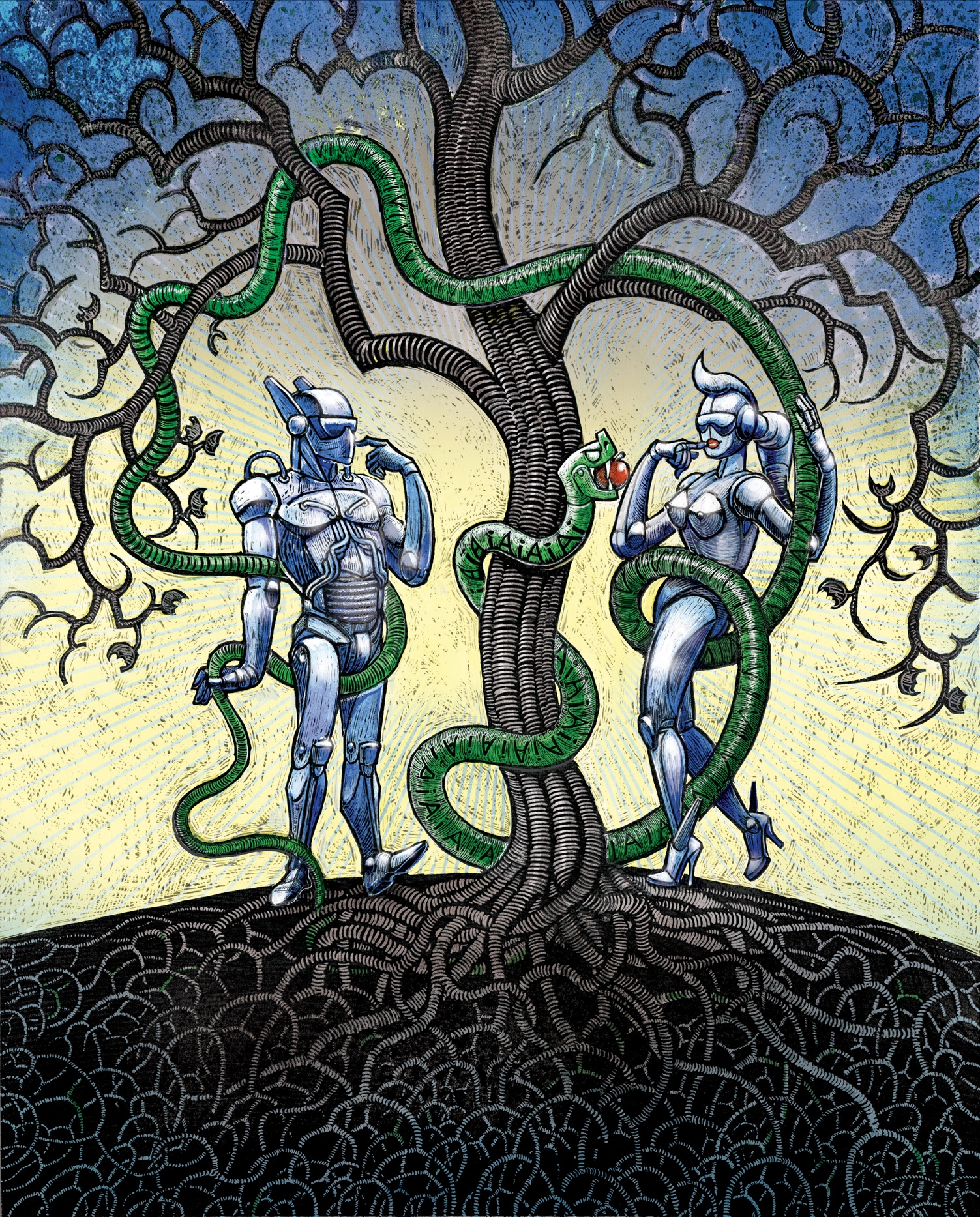

That so many attended, despite the storm outside, suggested expectations were running high for the Institute for Strategic Solutions’ annual Strategic Foresight gathering. The Ljubljana-based think-tank, operating since 2011, was launching the fourteenth edition of its publication The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight. The magazine’s cover features artwork by Ciril Horjak, the illustrator and comic artist who won Slovenia’s Prešeren Prize for achievement in the arts – his covers have become something of a staple for the publication.

The timing also felt pointed. Slovenia faces parliamentary elections in March. The Western Balkans inches towards the European Union’s self-imposed 2030 enlargement deadline – Montenegro and Albania furthest along in negotiations – whilst questions about where capital flows, whether European regulations enable or constrain growth, and who controls the digital infrastructure underpinning modern economies have moved from theoretical to immediate.

“The economy isn’t a competition in the classical sense, where some win and others lose,” said Tine Kračun, the institute’s director, opening the afternoon. “The goal is to create conditions where everyone can thrive.”

But it also depends on whether existing members like Slovenia can demonstrate that EU membership actually supports economic competitiveness rather than constraining it. Whether conditions currently support that ambition became the afternoon’s central tension.

Performance politics

Three days earlier, Trump had ordered Delta Force commandos into Venezuela to capture President Nicolás Maduro, a tactically impressive raid with no apparent plan for what comes next. Photographs from the Mar-a-Lago “war room” revealed administration officials monitoring the operation alongside a large screen displaying X.com with “Venezuela” searched, tracking public reaction in real time. These weren’t public servants executing policy. They were influencers managing content.

But whilst attention fixes on the stage, Stojan argued, processes unfold in the background that carry long-term consequences. He displayed a series of graphs tracking global manufacturing’s share of added value from 1995 to 2022. Across the room, phones emerged from pockets as attendees photographed the data: China’s line climbing from 4% to nearly 30%, the United States falling from 21% to 17%, the EU declining similarly. The other side of this story, he said, is security, visible most clearly in rising military expenditures and the militarisation of political discourse.

“Our message for 2026,” Stojan concluded. “Turn on your filters.”

Nejc Krevs, a young journalist and news anchor whose profile has risen steadily over the past few years, took over to steer the discussion that followed.

The capital question

Andrej Lasič, a board member at NLB, Slovenia’s largest bank, said the bulk of capital in the Western Balkans flows into construction, property and retail, all sectors with relatively low added value. “I’d like to see more investment in technology and high-value industries,” he said.

His observation reflects a broader challenge of how to move up the value chain when established sectors offer more predictable returns. Construction and retail require less specialised knowledge, face fewer regulatory hurdles, and generate faster cash flows than, say, software development or advanced manufacturing. But they also create fewer high-skilled jobs and contribute less to long-term productivity growth.

Lasič expressed optimism about EU accession prospects for Montenegro and Albania, but added that Brussels still “doesn’t fully understand the region,” which constrains development.

Slovenia has often held the reputation of being the Balkans’ gateway into Europe, its economy and institutions shaped by two decades inside the union, and Tamara Zajec Balažič, director of SPIRIT Slovenia, the national business development agency, leaned into that role. Slovenian companies remain competitive in the Western Balkans, particularly in logistics, information technology and manufacturing, she said, and the country is recognised internationally as adaptable, innovative, reliable. But the region still faces regulatory fragmentation, varying levels of transparency alongside often lengthy and complex administrative procedures.

Two decades inside the union have made Slovenia fluent in Brussels bureaucracy whilst geographic proximity and shared history keep it attuned to Balkan realities, enabling it to understand both sides of a disconnect that policymakers further west often miss.

Platform economics

Ivana Vrviščar, a board member at Pošta Slovenije, the state postal operator, broadened the discussion to examine structural changes in global capitalism. The economy is entering a new phase, she argued, one departing from classical free-market models. Digital platforms linked to e-commerce, cloud computing and data management now dominate, with infrastructure owners extracting rental income rather than competing on price or quality.

She described this as “technologically conditioned feudalism,” or, to borrow the term coined by Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister who battled EU creditors during the 2015 debt crisis, “technofeudalism.”

No one contested the diagnosis. The question wasn’t whether platform economics had fundamentally altered capitalism, but what established businesses could do about it.

Uroš Ivanc from Triglav Insurance, the region’s largest insurer, offered a pragmatic response. Business risks remain constant, he said, but understanding them creates space for innovation. The industry is developing new products to address technological, demographic and regulatory risks, increasingly deploying artificial intelligence to optimise processes and manage data. “Insurance possesses extensive databases which, properly processed, create added value for both clients and insurers.”

If you can’t compete with the platforms, the logic suggested, become more platform-like yourself.

Competing with one hand tied

The sharpest frustrations emerged when discussion turned to regulatory burden, specifically, whether European and national rules hamper competitiveness in globally exposed industries.

Dr Tomaž Vuk, chief executive of Alpacem Cement, spoke with the precision of someone who knows exactly what his industry requires and what stands in its way. Materials manufacturing competes in an environment without level playing fields, he said, where companies elsewhere operate under different environmental standards, labour protections, compliance costs.

Competitiveness requires systemic change, not just company-level improvements, Vuk argued. In the EU, where a directive agreed upon by all member states often ahs to take years before being implemented at a national leve, this sort of duplification appears unnecessary and wasteful, creating delays that last years.

Competitiveness requires systemic change, not just company-level improvements, Vuk argued. The region must accelerate decision-making if it wants to compete globally, yet in the EU, directives agreed by all member states still take years to filter down to national implementation, a duplication of process that creates delays competitors elsewhere don’t face.

Leaning forward when his turn came, Franc Dover, director of Pannonia Bio Gas, spoke with the kind of passion that suggested he was finally saying aloud what had been building for some time. Slovenia has significant but underutilised potential for energy self-sufficiency through waste management, where biogas plants can convert unsuitable maize, agricultural residues, animal manure, food waste into energy, turning what gets discarded into power. “But permit procedures can last several years,” he lamented.

Dover’s irritation felt more immediate, less resigned. The technical solutions exist. The economic case strengthens as energy prices rise and climate commitments tighten. What’s missing is institutional capacity to move from policy ambition to physical deployment. Governments announce ambitious renewable energy targets, then struggle to approve the infrastructure needed to meet them, approval processes stretching across years whilst competitors elsewhere simply build.

Outside, snow continued falling on Ljubljana, heavier now than when the afternoon began. Inside, the hundred people who’d chosen to attend despite the weather dispersed slowly, reluctant to leave the warmth, conversations continuing in clusters near the entrance.