Europe eyes Balkan potential to secure rare metals future

Maja Dragovic

As the global race for critical raw materials intensifies, the Western Balkans is emerging as a potential key player in Europe's quest for rare earth elements (REEs) - crucial components in modern technology and the green transition. The European Union, currently reliant on China for over 95% of its REE supply, is actively seeking ways to bolster its self-sufficiency. Recent studies and exploration efforts have unveiled significant REE potential across the Balkan region, catching the attention of both EU policymakers and mining companies.

At the forefront of this new drive is Serbia’s Jadar project, led by mining giant Rio Tinto. The project, which was previously halted due to environmental concerns, is now back on the table. Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić recently indicated that the government is preparing to give Rio Tinto the green light to develop what could become Europe’s largest lithium mine. The project is estimated to produce 58,000 tons of lithium per year, potentially meeting 17% of Europe’s electric vehicle production needs.

Exploring the full potential

But the region’s potential extends beyond lithium. Dr. Klemen Teran from the Geological Survey of Slovenia highlights the promising REE concentrations found in bauxite deposits across the Balkans, with some of the highest levels found in Slovenia.

“In Slovenia, there are over 30 smaller and currently economically unviable bauxite occurrences,” explains Teran. “Recent research indicates that most of these bauxites are highly enriched with REEs, reaching concentrations between 0.1% and 0.2%, among the highest in the Balkans.” While these concentrations are lower than those found in some global deposits, they represent a significant untapped resource.

The potential for REE extraction isn’t limited to new mining operations. Teran emphasises the value of reprocessing mining waste and secondary mineral resources. “The quantities of deposited materials are immense, and they contain significant amounts of valuable minerals,” he notes. “Over time, extraction technologies have advanced considerably – in the past, much richer ores were exploited compared to today – and the focus of extraction has shifted: elements that are very important today were once discarded in waste heaps, which can now serve as a source for these elements.”

This approach could not only yield valuable REEs but also address environmental concerns associated with existing mine waste. Moreover, the region could become a stronghold in reuse technologies and recycling processes. Slovenia, for instance, is home to Magneti Ljubljana, a magnet manufacturer that requires raw materials for production and possesses the capacity for recycling and refurbishing magnets. This exemplifies the potential for creating a circular economy within the REE sector.

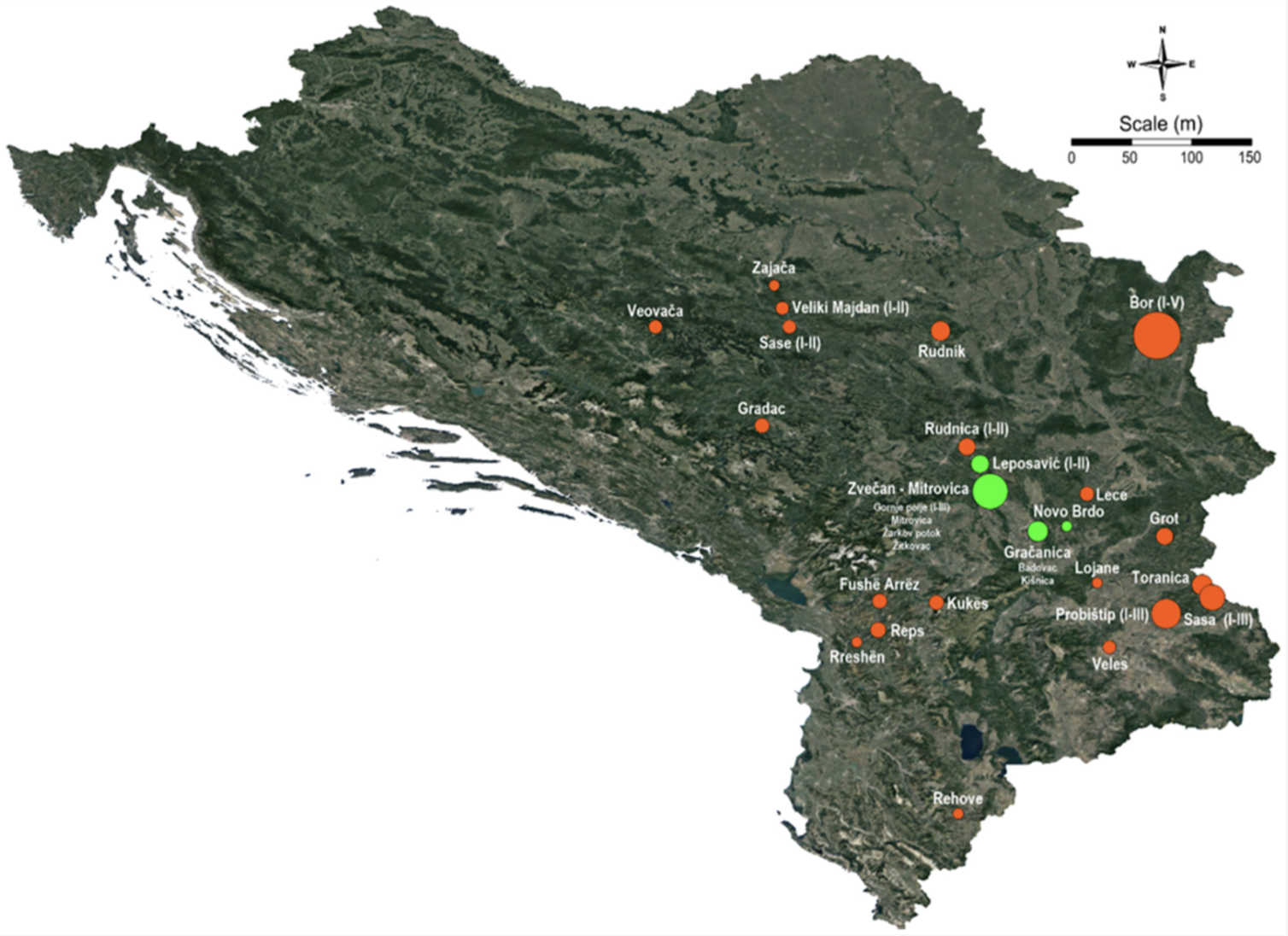

The region also holds promise in the reopening of closed mining sites. Many mines closed in the 1990s not due to ore depletion but because of economic and political factors. Teran points out that “Many former mines are now ripe for renewed exploration and potential reopening.” He points to several examples of successful mine revivals in the Balkans, such as the Rupice-Veovača mine in Bosnia and Herzegovina where lead, zinc, barite, copper, gold, and silver are being exploited or exploitation of copper and gold in Bor, Serbia.

There are also several closed mines in Slovenia that may be worth exploring, adds Teran. For instance, the lead and zinc Mine in Mežica that contains germanium, which is used in infrared optics, solar cells, and high-speed electronic components; or the Sitarjevec mine in Litija known for barite which is widely used in plastics industry. However, he cautions, “reopening a mine is a lengthy process, often spanning a decade and requiring substantial research and financial investment.”

There are other challenges, too. The relatively low REE content in many deposits compared to global standards makes economic extraction challenging. Moreover, there are significant concerns about environmental impacts and societal acceptance of mining activities. Gaining a “Social License to Operate” will be crucial for the success of these projects.

Locations of potentially prospective landfills – the size of the circle is proportional to the size of the SRM deposit. Source: www.mdpi.com

Rare opportunity

Despite these hurdles, the EU sees the Western Balkans as a key piece in its strategy to secure a stable supply of critical raw materials. The recently passed Critical Raw Materials Act (CRMA) sets ambitious targets for domestic sourcing and processing of these materials, and the Western Balkans could play a significant role in meeting these goals.

Initiatives like the RESEERVE project are paving the way for future development. By mapping mineral resources in the Western Balkans and creating a comprehensive mineral register, the project is integrating the region into a pan-European minerals intelligence network.

On a broader scale, the establishment of the Geological Service for Europe (GSEU) is underway, with active participation from the region. Slovenia is set to become the formal holder of the International Centre of Excellence for Sustainable Resource Management, further cementing the region’s role in Europe’s mineral resource strategy.

This would not only contribute to Europe’s REE supply chain but also boost local economies. Professor Vladimir Simić from the University of Belgrade’s Faculty of Mining and Geology emphasises the broader implications of this development.

“The Western Balkans must reindustrialise to survive,” he argues. “By industrialisation, I mean modern factories with zero CO2 emissions, competitive products, and well-paid workers. The Western Balkans could serve as a good example, showing that cooperation between states can be highly successful when the right goals are set.”