Putin-proofing Europe, one cow at a time

editor

Five years to turn farm waste into a strategic energy resource. On paper, the EU has a plan. On the ground, it has a problem.

The Adriatic Team

Somewhere in the flatlands of northeastern Slovenia, a digester is fermenting organic waste and chicken slurry into methane. The plant has been running since 2012. It’s one of two operated by Pannonia Bio Gas, which between them account for roughly half of Slovenia’s biogas output. Franc Dover, who took over as chief executive last year, can tell you exactly how many kilograms of food waste the average Slovenian throws away annually (more than 70), and exactly how much of that waste the country’s composting facilities can handle (not enough). He has spent the past year trying to figure out whether expansion makes sense. He is waiting for the government to tell him whether it’s possible.

This is the granular reality behind one of the European Union’s most ambitious energy targets: 35 billion cubic metres of biomethane by 2030. The number showed up in the REPowerEU plan in May 2022, three months after Russian tanks crossed into Ukraine, and it has been repeated in Brussels ever since. Thirty-five bcm. A sevenfold increase on current production and enough, in theory, to replace the gas that used to arrive from Siberia.

The logic behind it is sound. Biomethane is chemically identical to fossil gas, flows through the same pipes, burns in the same boilers, powers the same trucks. Unlike LNG shipments from Qatar or pipeline gas from Algeria, it doesn’t depend on shipping lanes, transit countries, or foreign policy. It’s produced locally, from local feedstock, and every cubic metre of it is one less cubic metre that needs to be imported. The geopolitical appeal is obvious. So is the climate case: biomethane captures methane that would otherwise escape from manure lagoons and landfills, turning a potent greenhouse gas into a usable fuel. Denmark already gets a quarter of its gas consumption from biomethane. Germany and Italy aren’t far behind.

But scale is the problem. Always the problem

“Europe has the technology, the feedstock, and the investment appetite,” says Piero Gattoni, president of the European Biogas Association. “Developers will only commit capital when the regulatory environment is consistent, predictable, and supportive across the value chain.” He ticks off the requirements: clear sustainability rules, faster permitting, support schemes that account for the wider benefits. Energy security. Waste management. Rural jobs. “Where these elements are in place, we see plants being built at record speed.”

Where they aren’t, nothing gets built at all.

The infrastructure question is just as knotty. Most biomethane plants are small, scattered across the countryside, hooked into low-pressure distribution grids near the farms and food factories that feed them. The European gas network, however, was designed to move molecules from big import terminals and production fields down to consumers. To hit 35 bcm, that logic has to reverse. Gas produced at the local level needs to flow upward into the high-pressure transmission system, and from there across borders.

The European Network of Transmission System Operators for Gas, or ENTSOG, which represents Europe’s gas transmission operators, calls this “reverse flow.” According to their latest network development plan, only two countries have formally planned for it: France and Denmark. Everyone else is still figuring it out. “In the case that any other region has such potential,” the plan notes, “the situation should be assessed by [transmission system operators] with their national authorities at country level.”

There are fiddlier problems, too. Biomethane can contain more oxygen than fossil gas, which affects its combustion characteristics. The EU’s principle is that such technical differences shouldn’t restrict cross-border flows, but harmonising specifications across 27 member states is slow work. The Guarantees of Origin system, which lets traders buy and sell biomethane certificates across Europe, depends on a Union Database that’s still under construction.

And then there’s Slovenia

Slovenia isn’t a major player in European biogas. Production is small and its ambitions sit somewhere between hopeful and irritated.

Dover came to Pannonia Bio Gas after years in public utilities and biofuels. He knows the compliance side, the procurement side, the part where you have to actually find the waste and get it to the digester. The inputs, he says, aren’t the problem. Slovenia produces more organic waste than it knows what to do with. Secondary crops that would otherwise rot in the field. Slurry from livestock operations. Supermarket stock past its sell-by date. Household scraps. Slovenians throw away a third of their food, and the composting system can’t absorb it. The digesters could.

The issue the industry faces in Slovenia, however, is that biogas cuts across traditional regulatory boundaries. It touches environment, energy, and agriculture, three ministries with three sets of priorities, and it doesn’t sit squarely in any of their briefs, creating a patchwork of rules that don’t quite fit together.

Then there’s the KOPOP scheme, a subsidy programme that pays farmers to adopt environmentally friendly practices. To stay eligible, farmers must follow strict rules on fertiliser use, and digestate counts against those limits. Digestate, the nutrient-rich residue left after fermentation, counts against those caps. Never mind that it’s organic, that it returns nitrogen to the soil without the carbon footprint of synthetic alternatives. On paper, it’s treated the same as the industrial stuff. Farmers who depend on KOPOP won’t risk their subsidies by taking it.

And then there’s NIMBYism, or “not in my back yard,” the reflexive opposition to any development that might affect the view from the kitchen window. Biogas has an image problem, most of it outdated. Modern plants are enclosed, the fermentation process is anaerobic, and the output is odourless methane. None of that matters much when a permit application lands on a village council’s desk. People hear “digester” and think of trucks, smells, industrial blight. The technical reality is rarely enough to overcome the gut reaction.

What it would take

A new law, ZSROVE-1, is expected next year, that would establish a dedicated support framework for renewable gases, setting out how biomethane producers get paid and under what terms they can connect to the grid. Industry groups have been pushing for what they call a “policy mix.” Subsidies to close the cost gap with fossil gas. Grants to help existing plants convert to biomethane production. A blending mandate that would require a minimum share of renewable gas in the grid, creating guaranteed demand.

Dover, in Dobrovnik, is cautiously optimistic. “We have the potential,” he says. “If we can cooperate at the national and local level, I see a win-win situation.” But he’s been here before. What he needs is simpler than policy papers make it sound. A proper legislative framework. Incentives that are actually attractive to investors. And some way past NIMBYism.

He’s old enough to remember what scarcity feels like. “Those of us who lived through the energy crisis in the twentieth century, independence, then the financial crisis, Covid, and now war on the EU’s doorstep – we know what self-sufficiency means. Energy, food, water, waste. When the sources narrow or disappear, you learn what matters.” He pauses. “We have to use every possible source for sustainable living and coexistence with nature. Biogas is one of the big ones.”

Business forum in Tirana signals deepening ties with Albania

editor

As Albania accelerates toward EU membership, Slovenian executives see a fast-growing market on the Adriatic’s eastern shore – and a chance to shape its trajectory.

The Adriatic Team

On a grey Wednesday morning in the Albanian capital, executives from some of Slovenia’s largest companies gathered in a conference room to discuss something that, a decade ago, might have seemed improbable: the rapid emergence of Albania as a serious destination for investment and strategic partnership.

The Slovenia-Albania Business Forum, organised by the Institute for Strategic Solutions (ISR), the Embassy of the Republic of Slovenia in Tirana, and the public agency SPIRIT Slovenia, brought together senior figures from banking, insurance, logistics, and manufacturing alongside Albanian counterparts. The centrepiece of the day was the signing of a memorandum of cooperation between SPIRIT Slovenia and Albania’s Investment Development Agency, AIDA, providing a framework intended to give bilateral economic ties a more formal architecture.

Albania’s real GDP growth reached 3.75 per cent in the third quarter of 2025, spread across virtually every sector. Tourism arrivals have surged by more than 80 per cent. Bilateral trade between the two countries has tripled over the past decade, reaching €108 million in 2024, while Slovenian direct investment in Albania climbed more than 30 per cent last year alone. For a small, open economy like Slovenia’s, these are numbers worth paying attention to.

Banking on the Balkans

Blaž Brodnjak, the chief executive of NLB, the region’s dominant banking group, framed the opportunity in terms of trajectory. NLB is the second-largest bank in both Kosovo and Serbia and ranks among the top three lenders across the Western Balkans, giving it an unusually comprehensive view of regional capital flows.

“This is a country with pronounced development ambition and a clear orientation toward transformation,” Brodnjak said. “The opportunities are significant, but they require a serious, strategic approach.” He identified the expansion of financial services – particularly lending to support foreign direct investment – as the area of greatest potential over the next two years.

Tedo Djekanović, the executive director responsible for subsidiary management at Triglav Group, Slovenia’s leading insurer, echoed the point from a different angle. As foreign capital arrives and local enterprises grow more complex, demand for sophisticated insurance products follows. “Local companies are aware of the challenges and are prepared to align with European legislation and processes,” he said, adding that demand for more complex coverage typically tracks the arrival of foreign investors.

“Treat us as equal partners”

The Albanian perspective, voiced most directly by Arben Shkodra, secretary general of the Albanian National Economic Council, carried a note of caution. The market, he warned, has no room for false assumptions or shortcuts outside official channels. Underestimating local entrepreneurs, he said, remains one of the most common mistakes foreign investors make.

“Albanian companies have rich experience and should be treated as equal partners, not merely as subcontractors,” Shkodra said.

Alban Zusi, co-founder and president of AZ Group, reinforced the message by outlining his company’s regional footprint. Closely connected to the markets of North Macedonia, Kosovo, and Montenegro, AZ Group sees Albania as a natural hub for building regional networks, a place where companies can pool capabilities and serve the broader Western Balkans market from a single base.

On the ground

The forum’s second panel shifted the conversation from macro-level opportunity to operational experience. Samo Kastelic, a board member of the logistics company Intereuropa, which has operated in Albania since 2009, described the country’s EU accession negotiations as a catalyst for growth in Adriatic and Central European transport corridors. “Albania’s entry into the European Union will also bring changes to Adriatic and Central European transport corridors,” Kastelic said, “with a clear objective of finding faster and more cost-effective routes for the flow of goods.”

Sergej Simoniti, director of Coface Slovenia and head of its Adriatic operations, underscored the role of transparency. Coface manages one of the world’s largest databases of corporate and market information, and Simoniti argued that reliable data sharing serves as the foundation for cross-border trust. “It is in the interest of both sides to share reliable and accurate data, as this builds trust and creates a safer environment for international business,” he said.

A practical partnership

Nataša Kos, deputy director of SPIRIT Slovenia, who signed the memorandum with AIDA’s Laura Saro, offered what amounted to the forum’s thesis statement. “Slovenia is not coming to Albania merely as a member of the European Union,” she said, “but as a practical partner with experience from the accession process, strong innovation potential, and a clear emphasis on execution and results.”

Inside Slovenia's push for carbon-neutral cement

editor

The cement industry today generates around 6% to 8% of all global CO₂ emissions, primarily due to the decomposition of limestone in the clinker production process, with a smaller share coming from kiln energy. Cement plants therefore play a crucial role in the decarbonisation of construction.

Jan Tomše

In Slovenia, this role is even more pronounced: Alpacem Cement is the country’s only domestic cement producer and one of the most technologically advanced companies in the region. It sees its mission as going well beyond traditional industrial modernisation: it aims to reshape the entire cement and concrete value chain and, in doing so, contribute to the decarbonisation of Slovenia’s infrastructure.

A progressive vision amid real-world challenges

European regulation demands rapid emissions reductions by 2040, yet the industry warns that implementation is lagging behind political ambition. “For the ambitions we have in Europe, we are simply too slow,” says Dr Tomaž Vuk, CEO of Alpacem Cement.

Spatial planning procedures and permitting can take between five and ten years – significantly longer than in Asia or the United States. This means that industry must start deploying new technologies now if it wishes to achieve decarbonisation in time.

Despite these constraints, Alpacem is betting on technological innovation and a phased approach that balances environmental impact, energy realities and the expectations of local communities.

Low-carbon cement, the core of the global transition

Low-carbon cement is becoming one of the most important levers for reducing emissions in construction. Progress is built on the following pillars:

- a reduced clinker factor, using mineral additions (slag, fly ash, calcined clays),

- improved energy efficiency, digitalisation and process optimisation,

- CCUS technologies – capture, utilisation and storage of CO₂ – the only way to eliminate process emissions from limestone.

According to recent technical reviews of lowcarbon cements, as well as industry case studies on CO₂reduced concretes and pilot projects using advanced blended cements, pilot projects around the world already demonstrate 30 to 60% lower emissions while maintaining the same loadbearing capacity and full compliance with standards. The main obstacles remain cost, the availability of raw materials and regulatory rigidity. This is why, for innovators such as Alpacem, systematically expanding the portfolio of lowcarbon products and preparing the ground for future technologies is essential.

Energy, materials and technology

A comprehensive transformation is under way at Anhovo, combining advanced energy solutions, lower-carbon cement through improved materials, research into carbon capture, transport and storage, and the development of new technologies.

Advanced energy solutions include installing solar power systems in the cement plant’s industrial area, gradually electrifying processes, and significantly reducing the share of fossil fuels in favour of biomass and alternative fuels.

For the next phase of the transition – especially CO₂ capture – industry will require two to three times more energy than today, and it must be clean. “If our competitor in Africa has cheaper energy, green cement will be cheaper there,” warns Dr Vuk. This clearly shows that energy has become a strategic driver of technological innovation.

Lower carbon footprint through advanced materials

Alpacem is already reducing the clinker content of its cements and increasing the use of mineral additions such as slag, ash and filter ash. This supports the development of new low-carbon cements in line with the European standards.

Because process emissions from limestone decomposition cannot be solved through optimisation alone, Alpacem is exploring options for carbon capture, transport and storage. This technology will be essential in the next stage of the transition, as cement plants cannot achieve net-zero emissions without it.

The transition depends on trust

Innovation is not only technological. A successful transition requires the support of local communities. “With transformations of this scale, we must be able to listen to one another. Without trust, every step will be endlessly questioned or blocked,” emphasises Dr Vuk.

Alpacem therefore pairs its technological development with ongoing dialogue with local residents, transparent communication on environmental impacts and cooperation with the state and environmental organisations. This recognises that decarbonising industry is a societal project, not merely an engineering one.

Advancing eco-friendly infrastructure in Slovenia

Cement remains a cornerstone of modern infrastructure: durable, fire-resistant and locally available. Concrete accounts for around 50% mass of Europe’s building stock, yet only 15% of its embodied energy, making it a key building block of the green transition. Wood and concrete are expected to evolve as complementary materials of the future.

The transformation of the Anhovo cement plant therefore carries broader significance: Slovenia can demonstrate that advanced industry, environmental goals and community dialogue can be successfully brought together. This creates a model that other energy-intensive industries can also adopt.

The road ahead: innovation, investment and clear policy signals

For the widespread adoption of low-carbon cement, the following will be crucial: the introduction of a green public procurement system, appropriate CO₂ pricing, and support for investments in state-of-the-art technology and CO₂ infrastructure.

Alpacem acts as an early adopter. The company is already lowering its clinker factor, expanding the use of alternative fuels, and increasing energy efficiency. All of this forms part of its long-term strategy aligned with the goal of carbon neutrality. Thanks to Alpacem, Slovenia now has a remarkable opportunity to position itself at the forefront of low-carbon construction in Europe.

NLB Skladi cements market lead as Gen Z turns to long-term saving

editor

Slovenia’s largest asset manager posted record results in 2025, capturing nearly half of the country’s net fund inflows. Its success coincides with the broader trend of young investors entering markets earlier than any previous generation.

Andraž Tavčar

NLB Skladi, the asset management arm of Slovenia’s largest banking group, has reinforced its dominant position in the domestic investment market. The company announced on 22 January that its umbrella fund reached €3.0 billion in assets under management by the end of 2025, serving nearly 103,000 investors. When combined with discretionary portfolio management, alternative investment funds, and regional subsidiaries in North Macedonia and Serbia, total assets under the NLB Skladi umbrella now exceed €3.7 billion.

“2025 was a record year for NLB Skladi,” said Luka Podlogar, president of the management board. “With net sales of €245.5 million and a nearly 46 per cent share of net sales in the Slovenian market, we have further strengthened our position as the largest asset management company in Slovenia.”

The firm is bullish on 2026. “At NLB Skladi, we are maintaining an above-average exposure to equities compared to bonds this year, and we prefer both asset classes to cash,” said Rok Potočnik, a senior portfolio manager at the company. He pointed to tailwinds including rapid advances in artificial intelligence, strong US productivity growth, expectations of more expansionary fiscal policy, and low levels of corporate and household debt. Volatility may rise, Potočnik added, but that presents opportunities for investors willing to deploy capital during market dips.

A generation investing earlier

NLB Skladi’s record year arrives against a backdrop of shifting demographics in retail investing worldwide. The World Economic Forum’s Global Retail Investor Outlook, a survey of investors across 13 economies published last year, found that 30 per cent of Gen Z – broadly, those born between the late 1990s and early 2010s – began investing in early adulthood. That compares with just 9 per cent of Gen X and 6 per cent of baby boomers who started at the same life stage.

The gap widens when it comes to financial education. By the time they enter the workforce, 86 per cent of Gen Z have already learned about personal investing, the survey found, versus 47 per cent of boomers. Younger generations are also more open to technology-assisted advice: 41 per cent of Gen Z and millennials said they would allow an AI assistant to manage their investments, compared with 14 per cent of baby boomers.

A separate study from the Oliver Wyman Forum, published in January 2026 and based on data from 300,000 investors tracked since 2020, found that economic anxiety is accelerating the trend. Many young people, uncertain about job security in an era of artificial intelligence and automation, are turning to markets as a hedge. Social media plays an outsized role in this shift, with more than half of Gen Z and 44 per cent of millennial investors citing it as the primary reason they began investing.

NLB Skladi appears to recognise the opportunity. A significant portion of its 2025 activity was devoted to a financial literacy campaign aimed at young Slovenians, framing saving not as privation but as a means to realise aspirations.

“Although we talk about money, we are really talking about feelings – security, freedom, and meaning,” said Blaž Bračič, a member of the NLB Skladi management board. He added that the firm’s role was to help young people see saving as an instrument for achieving their goals rather than a form of self-denial.

The message aligns with what researchers are finding. The WEF survey noted that nearly 20 per cent of Gen Z non-investors cited distrust of financial institutions as their reason for staying out of markets. Among those who do invest, a majority said they would invest more if they had greater trust in their platforms and better access to education. For traditional asset managers competing against slick fintech apps and social media influencers, credibility and clear communication may matter as much as returns.

In it for the long haul

NLB Skladi is also positioning itself around Slovenia’s new individual investment accounts, which come into effect later this year. “Individual investment accounts represent a structured and tax-efficient framework for long-term goals, and a good first step toward a personal financial plan,” Bračič said. “They are also a wake-up call for everyone who is not yet saving for the future.”

For now, the firm’s record year suggests it is well placed to benefit from whatever growth materialises, both at home and across the region. NLB Skladi offers 20 sub-funds under its umbrella structure, spanning global equities, emerging markets, bonds, and sector-specific strategies. Its distribution network, tied to NLB’s extensive branch presence, gives it reach that smaller competitors struggle to match.

And if the generational data holds, the pipeline of new investors may only grow. A cohort that starts saving in its early twenties, with decades of compounding ahead, represents a long-term opportunity. Provided the industry can earn their trust.

ISR gathers leaders on capital and competitiveness

editor

Discussion surfaces tensions between Brussels frameworks and regional realities at Strategic Foresight event.

Andraž Tavčar

Outside the Ljubljana City Museum on Tuesday afternoon, snow fell steadily across the city centre, the kind of sustained winter weather the Slovenian capital hasn’t seen in years. Inside the museum’s intimate cinema-style conference space, roughly a hundred people brushed flakes from their coats, collected glasses of wine, and exchanged New Year’s greetings before settling into their seats.

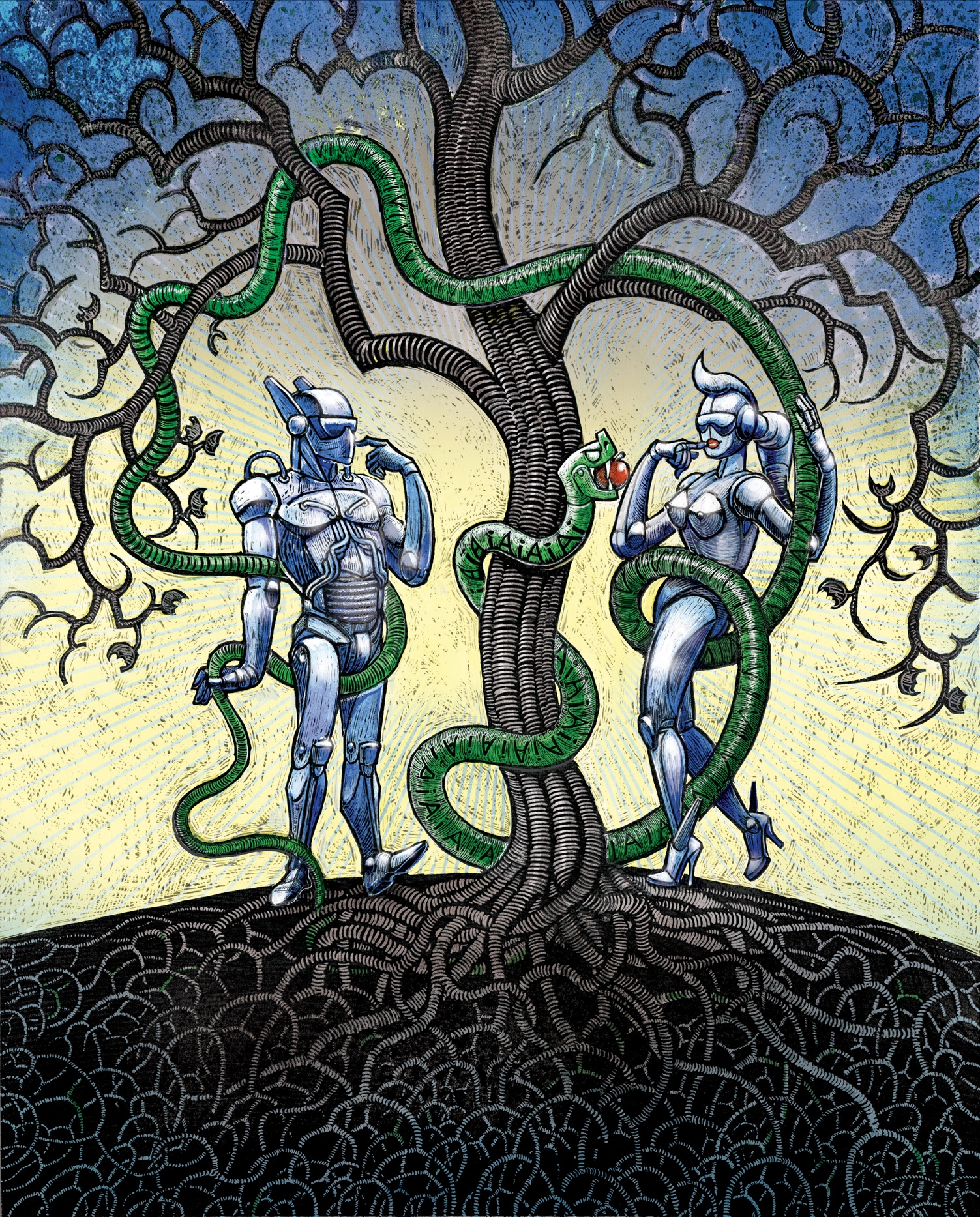

That so many attended, despite the storm outside, suggested expectations were running high for the Institute for Strategic Solutions’ annual Strategic Foresight gathering. The Ljubljana-based think-tank, operating since 2011, was launching the fourteenth edition of its publication The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight. The magazine’s cover features artwork by Ciril Horjak, the illustrator and comic artist who won Slovenia’s Prešeren Prize for achievement in the arts – his covers have become something of a staple for the publication.

The timing also felt pointed. Slovenia faces parliamentary elections in March. The Western Balkans inches towards the European Union’s self-imposed 2030 enlargement deadline – Montenegro and Albania furthest along in negotiations – whilst questions about where capital flows, whether European regulations enable or constrain growth, and who controls the digital infrastructure underpinning modern economies have moved from theoretical to immediate.

“The economy isn’t a competition in the classical sense, where some win and others lose,” said Tine Kračun, the institute’s director, opening the afternoon. “The goal is to create conditions where everyone can thrive.”

But it also depends on whether existing members like Slovenia can demonstrate that EU membership actually supports economic competitiveness rather than constraining it. Whether conditions currently support that ambition became the afternoon’s central tension.

Performance politics

Three days earlier, Trump had ordered Delta Force commandos into Venezuela to capture President Nicolás Maduro, a tactically impressive raid with no apparent plan for what comes next. Photographs from the Mar-a-Lago “war room” revealed administration officials monitoring the operation alongside a large screen displaying X.com with “Venezuela” searched, tracking public reaction in real time. These weren’t public servants executing policy. They were influencers managing content.

But whilst attention fixes on the stage, Stojan argued, processes unfold in the background that carry long-term consequences. He displayed a series of graphs tracking global manufacturing’s share of added value from 1995 to 2022. Across the room, phones emerged from pockets as attendees photographed the data: China’s line climbing from 4% to nearly 30%, the United States falling from 21% to 17%, the EU declining similarly. The other side of this story, he said, is security, visible most clearly in rising military expenditures and the militarisation of political discourse.

“Our message for 2026,” Stojan concluded. “Turn on your filters.”

Nejc Krevs, a young journalist and news anchor whose profile has risen steadily over the past few years, took over to steer the discussion that followed.

The capital question

Andrej Lasič, a board member at NLB, Slovenia’s largest bank, said the bulk of capital in the Western Balkans flows into construction, property and retail, all sectors with relatively low added value. “I’d like to see more investment in technology and high-value industries,” he said.

His observation reflects a broader challenge of how to move up the value chain when established sectors offer more predictable returns. Construction and retail require less specialised knowledge, face fewer regulatory hurdles, and generate faster cash flows than, say, software development or advanced manufacturing. But they also create fewer high-skilled jobs and contribute less to long-term productivity growth.

Lasič expressed optimism about EU accession prospects for Montenegro and Albania, but added that Brussels still “doesn’t fully understand the region,” which constrains development.

Slovenia has often held the reputation of being the Balkans’ gateway into Europe, its economy and institutions shaped by two decades inside the union, and Tamara Zajec Balažič, director of SPIRIT Slovenia, the national business development agency, leaned into that role. Slovenian companies remain competitive in the Western Balkans, particularly in logistics, information technology and manufacturing, she said, and the country is recognised internationally as adaptable, innovative, reliable. But the region still faces regulatory fragmentation, varying levels of transparency alongside often lengthy and complex administrative procedures.

Two decades inside the union have made Slovenia fluent in Brussels bureaucracy whilst geographic proximity and shared history keep it attuned to Balkan realities, enabling it to understand both sides of a disconnect that policymakers further west often miss.

Platform economics

Ivana Vrviščar, a board member at Pošta Slovenije, the state postal operator, broadened the discussion to examine structural changes in global capitalism. The economy is entering a new phase, she argued, one departing from classical free-market models. Digital platforms linked to e-commerce, cloud computing and data management now dominate, with infrastructure owners extracting rental income rather than competing on price or quality.

She described this as “technologically conditioned feudalism,” or, to borrow the term coined by Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister who battled EU creditors during the 2015 debt crisis, “technofeudalism.”

No one contested the diagnosis. The question wasn’t whether platform economics had fundamentally altered capitalism, but what established businesses could do about it.

Uroš Ivanc from Triglav Insurance, the region’s largest insurer, offered a pragmatic response. Business risks remain constant, he said, but understanding them creates space for innovation. The industry is developing new products to address technological, demographic and regulatory risks, increasingly deploying artificial intelligence to optimise processes and manage data. “Insurance possesses extensive databases which, properly processed, create added value for both clients and insurers.”

If you can’t compete with the platforms, the logic suggested, become more platform-like yourself.

Competing with one hand tied

The sharpest frustrations emerged when discussion turned to regulatory burden, specifically, whether European and national rules hamper competitiveness in globally exposed industries.

Dr Tomaž Vuk, chief executive of Alpacem Cement, spoke with the precision of someone who knows exactly what his industry requires and what stands in its way. Materials manufacturing competes in an environment without level playing fields, he said, where companies elsewhere operate under different environmental standards, labour protections, compliance costs.

Competitiveness requires systemic change, not just company-level improvements, Vuk argued. In the EU, where a directive agreed upon by all member states often ahs to take years before being implemented at a national leve, this sort of duplification appears unnecessary and wasteful, creating delays that last years.

Competitiveness requires systemic change, not just company-level improvements, Vuk argued. The region must accelerate decision-making if it wants to compete globally, yet in the EU, directives agreed by all member states still take years to filter down to national implementation, a duplication of process that creates delays competitors elsewhere don’t face.

Leaning forward when his turn came, Franc Dover, director of Pannonia Bio Gas, spoke with the kind of passion that suggested he was finally saying aloud what had been building for some time. Slovenia has significant but underutilised potential for energy self-sufficiency through waste management, where biogas plants can convert unsuitable maize, agricultural residues, animal manure, food waste into energy, turning what gets discarded into power. “But permit procedures can last several years,” he lamented.

Dover’s irritation felt more immediate, less resigned. The technical solutions exist. The economic case strengthens as energy prices rise and climate commitments tighten. What’s missing is institutional capacity to move from policy ambition to physical deployment. Governments announce ambitious renewable energy targets, then struggle to approve the infrastructure needed to meet them, approval processes stretching across years whilst competitors elsewhere simply build.

Outside, snow continued falling on Ljubljana, heavier now than when the afternoon began. Inside, the hundred people who’d chosen to attend despite the weather dispersed slowly, reluctant to leave the warmth, conversations continuing in clusters near the entrance.

The logistics of integration

editor

Intereuropa manages freight across nine countries in southeastern Europe. Its strategy depends on borders becoming easier to cross.

Andraž Tavčar

Every week, freight trains and lorries move automotive parts, pharmaceuticals, and consumer goods from the Adriatic coast into the Western Balkans, a region where economic growth has outpaced Western Europe in recent years, but where logistics infrastructure has struggled to keep pace.

For Intereuropa, a Slovenian logistics firm with operations across nine countries in southeastern Europe, this gap represents both challenge and opportunity.

Global freight markets remain volatile. Container prices have eased from pandemic peaks, but demand is uneven, geopolitical tensions continue to disrupt trade routes, and logistics providers face sustained pressure on margins. Companies operating in the region must coordinate customs, warehousing, and transport across jurisdictions with differing regulations and uneven infrastructure.

Intereuropa has moved beyond traditional transport and customs clearance, developing more complex services in recent years, comprising warehousing, distribution, last-mile delivery. “Customers increasingly expect solutions tailored to their processes,” says Samo Kastelic, who joined Intereuropa’s management board in September after holding leadership positions at international logistics firms. The company operates twelve subsidiaries and manages over 260,000 square metres of logistics infrastructure across the former Yugoslav space.

That regional footprint, Kastelic argues, gives Intereuropa a structural advantage. Multinational clients operating across southeastern Europe can work with a single provider rather than coordinating separate contractors in each country. The company handles customs clearance, warehousing, distribution, and final delivery, or what the industry calls end-to-end logistics.

Warehousing expansion and high-value freight

Intereuropa’s recent investments have focused on capacity and service depth rather than geographic expansion. The company opened a logistics centre at Kukuljanovo, near the Croatian port city of Rijeka, and acquired additional storage facilities at Novi Banovci outside Belgrade. Combined with existing infrastructure across the region, total warehousing capacity now exceeds 260,000 square metres.

But warehousing alone is not the business. The company has shifted toward sectors where complexity commands higher margins. Pharmaceuticals require temperature-controlled storage and regulatory compliance. Food distribution demands tight delivery windows. Hazardous materials and oversized cargo need specialised handling expertise.

“We have strategically focused on certain industries and types of goods that require a high level of handling conditions, which also bring more added value,” Kastelic says. “Pharmaceuticals, food, retail, oversized cargo, dangerous goods.”

The logic is straightforward. Commodity freight is price-sensitive. Specialised logistics, tailored to specific industries and their regulatory requirements, offer more durable returns. Intereuropa expects that clients will value and invest in reliability and coordination in a region where these qualities are still hard to ensure.

The company also works extensively with automotive manufacturers, managing parts distribution for several major brands through its network. The Port of Koper, Slovenia’s sole maritime gateway, serves as the primary entry point for goods destined for the Balkan hinterland, and Intereuropa’s infrastructure is designed to connect that port to markets across the region.

Rail freight and the Koper-Belgrade corridor

In 2024, Intereuropa launched a regular rail freight service between Koper and Belgrade, a twice-weekly connection designed to offer an alternative to road haulage.

The service reflects broader shifts in European freight policy. The EU has pushed for modal shift from road to rail as part of its decarbonisation agenda, and logistics providers are under pressure to reduce emissions across their operations. Rail is slower than air, but faster than road over long distances, and produces a fraction of the carbon emissions per tonne-kilometre.

“We moved part of our freight flow from road to rail,” Kastelic says. “Price competitiveness and level of service are decisive, alongside the environmental impact.”

The commercial case for rail depends on reliability and price competitiveness. If trains run on schedule and costs remain below road haulage, clients will shift volumes. If delays mount or pricing advantages erode, the incentive disappears. Intereuropa frames the Koper-Belgrade service as proof of concept and as a demonstration that intermodal freight can work in a region where rail infrastructure has historically lagged.

The company is also developing last-mile delivery capabilities to complement its rail and warehousing operations. The goal is full supply chain coverage. Goods arrive at Koper by sea, move by rail to regional hubs, are stored and processed in Intereuropa’s warehouses, and reach final customers via the company’s distribution network.

Digitisation and operational flexibility

Kastelic emphasises that physical infrastructure alone is insufficient. Without information systems capable of tracking shipments, coordinating customs documentation, and providing clients with real-time visibility, logistics networks cannot function efficiently.

“Appropriate information support plays an extremely important role in the quality execution of logistics processes,” he says. “Without it, it is practically impossible to imagine doing business.”

Intereuropa has invested in upgrading its core IT platforms, developing new systems for parcel distribution, and integrating data flows across its subsidiaries. The company maintains an in-house development team that works directly with clients to design bespoke solutions, tracking systems, inventory management, delivery scheduling tailored to specific supply chains.

The emphasis on flexibility reflects market conditions, as freight volumes fluctuate with economic cycles, trade policies shift unpredictably, and geopolitical disruptions can reroute supply chains overnight. Logistics providers must absorb these shocks without passing excessive costs to clients.

Container prices, though lower than their 2021–22 peaks, remain volatile. Demand in Western Europe has softened, while southeastern European markets continue to grow. Intereuropa’s regional focus positions it to benefit from that divergence, but only if it can adapt quickly to changing flows.

“We closely monitor conditions and strive to operate very flexibly,” Kastelic says. “We redirect transport capacity according to the structure and flows of freight.”

Outlook

Intereuropa plans to continue expanding warehousing capacity across the region, with particular focus on e-commerce fulfilment, where demand has grown rapidly and logistics requirements differ from traditional freight. The company already operates a fulfilment centre in Dravograd, Slovenia, and sees potential for similar facilities elsewhere in its network.

Investment in IT will also continue. The company is developing platforms for parcel distribution and upgrading applications that support core logistics processes. Kastelic describes digital capability as a competitive differentiator, one that allows Intereuropa to offer services smaller regional competitors cannot match.

The broader outlook depends on factors beyond any single company’s control. Southeastern Europe’s integration into European supply chains continues, but unevenly. EU infrastructure funding has flowed into the region, though project delivery remains inconsistent. Border procedures have improved in some corridors and stagnated in others.

Intereuropa’s strategy assumes that economic integration will proceed, that freight volumes will continue growing, and that clients will value reliability enough to pay for it. “Southeastern Europe has significant potential,” Kastelic says. The twice-weekly train from Koper to Belgrade keeps running, and the company is betting that more will follow.

Can Slovenia stay ahead in the cyber arms race?

editor

As artificial intelligence gains the power to generate lifelike videos of executives or mimic co-workers’ voices to authorise urgent transfers, the challenge of protecting even the most basic digital interactions has never been more daunting.

The Adriatic Team

Generative AI is transforming cyber-attack capabilities in 2025, allowing criminals to automate and scale operations with unprecedented sophistication. Tools once reserved for seasoned hackers now help even modestly skilled actors probe system weaknesses, refine phishing lures and generate deepfake scams, dramatically widening the attack surface.

The weakest link is also the strongest

AI makes it trivially easy for attackers to fabricate credible identities and manipulate employees. The human element, long the weakest link, has thus become the main theatre of cyber war. Analysts reckon that human error, whether born of ignorance or inattention, lies behind roughly a fifth of all security incidents. Yet individuals are also an organisation’s most potent defensive asset.

How to reinforce that line? Technology alone will not suffice. Knowledge has become the truest antivirus. Understanding how attackers operate, spotting the tell-tale signs of social engineering and recognising deepfake trickery allows users to thwart most attacks before they cause damage. This must be backed by strict organisational policies: identity checks for unusual requests, unwavering use of multifactor authentication and regular updates of security protocols are the hygiene necessities of the digital era.

5G and AI

The same AI powering ever more refined attacks has become indispensable to defenders. Leading Slovenian operators, including Telekom Slovenije, the country’s largest telecoms provider, use it to design more resilient networks and detect suspicious patterns in real time. Historically, cyber-attacks required considerable expertise and manual effort – today AI has lowered entry barriers even as it strengthens some defences. The technology itself is neutral, but its effect depends on who wields it.

So it goes with 5G. As the network expands, soon expected to blanket nearly all of Slovenia, with Telekom already covering almost the entire population, the ecosystem grows more complex. Yet 5G also enables new layers of security. Smart, responsive networks with protections baked into their core let firms build bespoke private networks tailored to their risk profile.

To manage these risks, infrastructure providers have built round-the-clock cyber-security centres. Increasingly, security is shifting away from users’ devices and deeper into the network. Safe Web, a service from Telekom used by more than 150,000 subscribers, blocks malicious content before it reaches the user.

Slovenia’s advantage

Data from ENISA, the EU’s cyber-security agency, suggest that Slovenia ranks among the bloc’s more digitally secure members. It isn’t starting from scratch. The country boasts the highest number of AI researchers per head in the EU, strong internet infrastructure and extensive e-government services. Its innovation, however, remains concentrated in pockets of the economy, often within the domestic operations of multinationals. The challenge is diffusion rather than capability.

Still, Slovenia has long recognised that technological sophistication matters for economic performance. It has updated its research and innovation policies and nudged its Digital Economy and Society Index ranking to 13th by 2024, a sign of sustained investment in digital infrastructure and services.

But Slovenia’s favourable position is hardly assured. Collaboration among national operators, government bodies and private firms is becoming crucial. Only by sharing information on threats in real time can the country detect and thwart attacks effectively. Digital security is not a destination but a perpetual process of adaptation. An endless race against ever more inventive adversaries.

Who would dare board a plane piloted by artificial intelligence?

editor

At the event 404 Error: Truth Does Not Exist, organised by the Institute for Strategic Solutions and hosted at Triglav Lab, speakers discussed how to distinguish reality from disinformation and manipulation at a time when technology is advancing at an astonishing pace — and what role companies in the financial, healthcare, logistics and telecommunications sectors can play in strengthening trust in data and its security.

The Adriatic Team

“Across all levels of society we need to reflect on the consequences of extremely rapid technological development. Social change happens faster than it appears, which is why continuous learning, understanding technology and thinking about reskilling and upskilling the workforce are essential. Regulators and politicians are often incompetent and unaware of what is really happening, so they fail to adopt adequate measures. The rise of artificial intelligence will likely catch them off guard,” stressed AI expert Marko Grobelnik.

According to Tine Kračun, Director of the Institute for Strategic Solutions (ISR), which organised the event, it is crucial — in an era when technologies can convincingly imitate a person’s voice, face or writing style and blur the line between truth and fabrication — to establish mechanisms that help identify real information and distinguish it from disinformation.

Dr Jure Stojan, Partner and Director of Research and Development at ISR, said history teaches us two important lessons about modern technologies. First, we can anticipate which human needs a new technology will try to satisfy, but we cannot even begin to predict the form it will take. And second, we can predict how human shortcomings will manifest whenever new technologies are introduced. “Every technology that was expected to ease human work — the very promise under which it was marketed — ended up creating even more work for people,” Dr Stojan noted.

We cannot reduce truth to a collection of isolated facts, because facts without context create no meaning. True understanding only emerges through reflection, connection and interpretation, explained futurist and researcher Andraž Bole. At the core of so-called cognitive resilience is the ability for analytical and systemic thinking. Instead of accepting information at face value, we should break problems down to first principles, recognise relationships between phenomena and distinguish what is essential from what is not, Bole emphasised.

If we are not fast enough, technology will decide for us

Professor Marko Grobelnik of the Jožef Stefan Institute’s AI Laboratory warns that artificial intelligence is still too often seen as an enhanced version of existing tools, when in fact it is creating an entirely new social and technological reality. Its exponential growth is rapidly reshaping fields ranging from labour markets to the information landscape. The newest models, such as Gemini 3, GPT-5.1 and Grok 4.1, and the deployment of autonomous taxis like Waymo, are already replacing entire professions. At the same time, the traditional idea of work as the basis of livelihood is collapsing, and shared social reality is fragmenting under the pressure of information bubbles, deepfakes and synthetic propaganda.

Society will need to redefine the value of human beings, the responsibilities of autonomous systems and the infrastructure of truth — otherwise technology itself will shape social consensus, for the benefit of only a few. Grobelnik stresses that a thoughtful social response, education about technology and accelerated reskilling are all essential. Regulators and politicians are generally lagging behind and will likely be surprised by the changes AI brings.

Humans in a dual role

Maja Javoršek, Director of Compliance at Zavarovalnica Triglav, underlined that in the insurance sector, data is the foundation of business, legality and trust — yet most incidents are caused by people. Despite technical protections, mistakes arise from carelessness, weak passwords, curiosity or ignoring warnings. Statistics show that human error accounts for 95% of security incidents and two-thirds of data-security breaches. Yet people are also the strongest defence. Regular training, awareness-raising, attack simulations and clear, simple rules significantly reduce risks. What is essential is a security culture that combines technology and psychology: employees must understand their responsibility and the impact of their actions. The key message remains: humans are both the biggest risk and the most important defender — the difference lies in knowledge, attention and responsible behaviour.

Cyber attacks evolve faster than defence

Dalibor Vukovič, Strategic Lead for Cybersecurity Solutions at Telekom Slovenije, presented the example of a night-time attack on a Slovenian manufacturing company. Attackers used stolen data to enter the internal network, but a fast and professionally executed response limited the attack to just seven minutes and prevented millions in potential damage. Cyber threats, Vukovič said, most often occur at night or during holidays. Visibility over network activity is crucial; without it, companies often fail to detect an attack at all. Cybersecurity is only effective when it has management support and when defence teams think as dynamically as the attackers. “Attackers advance far more quickly than defensive technologies. Cyber protection is not a passing trend — it is something we genuinely need. This also applies to mobile phones, where without advanced protection we are extremely vulnerable,” Vukovič warned.

Who would dare get on a plane piloted by AI?

“Artificial intelligence acts like a crutch for our minds — it makes us limp a little all the time. Critical thinking and cultivating a healthy sense of doubt must therefore become part of our daily behaviour. Assigning responsibility is crucial. Give people the tools, knowledge and skills they need, but also make them accountable. People must understand they are responsible for the outcomes of their work,” stressed Maja Javoršek.

Dr Franc Bračun, Management Board Adviser at NLB responsible for data and artificial intelligence, said that in the bank’s experience, people — especially in recent times — place too much trust in technology. A growing challenge, he noted, is protecting against attacks on identity. The prerequisite for security is systemic protection. Defence against risk must be built on strong technical measures. Another important principle is that all critical decisions should be made by humans, not AI. “Who today would dare get on a plane that is flown not by a human, but by a machine?” he asked. The third key measure is education, which is essential for building resilience — a priority focus at NLB.

How AI became part of the team

Slavko Ovčina, Director of ICT Solutions at Pošta Slovenije, described the example of Pia, a voice assistant that understands all Slovenian dialects and is built on the latest advances in artificial intelligence. Pia enables customers of Pošta Slovenije to speak naturally in Slovenian, ensures fast and effective communication nationwide, improves user experience, shortens response times and sets new standards in digital communication. “If, during development, we had fully realised all the risks associated with AI, Pia probably would not exist today. We optimised her gradually along the way. People accepted Pia as part of the team, and thanks to her we have improved and shortened numerous processes,” Ovčina said.

People are central to cyber defence

editor

At a conference organised last week by the Institute for Strategic Solutions (ISR), Error 404: Truth does not exist, and hosted at Triglav Lab, Maja Javoršek from Zavarovalnica Triglav discussed the increasingly important role of people in safeguarding data and preventing cyber incidents across the financial and insurance sectors.

The Adriatic Team

Speaking about broader industry trends, she noted that human behaviour remains one of the key variables in cybersecurity everywhere—not just in insurance and not specifically at Triglav. “Across sectors, many security incidents involve an element of human error,” she said, emphasising that this reflects normal workplace pressures rather than intentional misuse. These errors typically arise because people work quickly, multitask or encounter unfamiliar digital threats, and they are observed in organisations of all sizes.

Javoršek stressed that the insurance industry’s reliance on data makes awareness especially important. More than 5.000 employees in Triglav, handle a wide spectrum of information governed by strict legal frameworks, including GDPR, sectoral regulations and internal compliance standards. “Insurance depends on trust, and trust depends on responsible data management,” she told the ISR audience.

In describing Triglav’s approach, she highlighted that the company uses well-established technical, legal and organisational safeguards such as regular patching, monitoring tools, penetration testing and global threat analysis. But she also pointed out that technology alone cannot eliminate risk if users are not prepared for the kinds of tactics attackers employ.

Building practical readiness

For this reason, Triglav focuses strongly on awareness and preparedness. Employees receive ongoing training, internal communication and visual reminders about safe digital practices. The company also conducts simulated phishing and social-engineering exercises to help staff recognise and respond to real-world attack patterns. “The purpose is not to expose individuals,” Javoršek explained, “but to strengthen practical readiness and make the right response feel natural.”

Her remarks also addressed the wider Slovenian context. Data from SI-CERT shows that reported cyber incidents have increased by more than a third between 2020 and 2024, affecting not only large enterprises but also smaller organisations that often have more limited resources dedicated to cybersecurity. To support these organisations, Triglav offers Cyber Protection Insurance, which provides expert assistance, forensic analysis, legal and reputational support, data restoration and coverage for business interruption or extortion attempts.

Javoršek emphasised that while prevention remains essential, handling the aftermath of an incident is equally important. “When an attack occurs, the quality of the response has a major impact on how quickly an organisation can regain stability,” she said.

She emphasised that cybersecurity is a shared responsibility: technology, governance and individual awareness must all work together. In her words, “Secure systems don’t depend only on tools, they also depend on people who understand the value of the information they work with.”

Alpacem Cement targets energy efficiency amid Slovenia’s broader transition

editor

Cement production is among the most energy-intensive industrial processes, consuming vast amounts of heat and electricity from quarry to kiln. For Alpacem Cement, d.d., Slovenia’s leading cement producer, improving energy efficiency has become both an operational and strategic priority.

The Adriatic Team

The company reports an annual electricity consumption of around 130 GWh, comparable to that of a small town. To better manage this, Alpacem has introduced an Energy Management System (EMS), providing a detailed overview of energy use across the plant and allowing tighter control of costs and performance.

In parallel, the firm has upgraded its SCADA system for heating and cooling control, enabling more precise regulation and improved efficiency. It is also expanding its use of renewables: its installed solar capacity now totals 3.72 MW, generating about 3,700 MWh of green electricity per year and cutting emissions by roughly 1,682 tons of CO₂. Plans are underway to add another 15 MW of capacity on the industrial site within the next three years.

Beyond renewables, Alpacem is examining waste-heat recovery options for both process heating and electricity generation using an Organic Rankine Cycle (ORC) system.

Lower emissions

Energy efficiency forms a core part of the company’s decarbonisation strategy, which also includes reducing clinker content – the most energy-demanding component of cement – to an average of 72 %, below the European average of around 75 %. The company is also increasing the use of recycled mineral raw materials and alternative fuels, in line with circular-economy principles.

Alpacem is further engaging in carbon-capture, utilisation and storage (CCUS) research, preparing feasibility studies and project documentation for future technology implementation and EU funding opportunities.

“The future of energy self-sufficiency and the transition to a low-carbon economy depend on close cooperation between industry, science, and policymakers,” said Dr Tomaž Vuk, President of the Management Board of Alpacem Cement. “Only coordinated action can deliver effective systemic solutions. For energy-intensive industries such as cement production, a strengthened and predictable regulatory framework is essential – one that promotes the circular economy, the use of secondary raw materials, and provides effective support mechanisms at the national level.”

Alpacem’s activities come at a time when Slovenia’s energy landscape is shifting. According to the Statistical Office, renewables accounted for about 25 % of gross final energy consumption in 2023, while national policies increasingly promote industrial energy efficiency, digital monitoring, and decarbonisation incentives.

As energy costs and regulatory expectations rise, Alpacem’s efficiency programme illustrates how industrial producers are adapting within Slovenia’s evolving energy framework, combining technical upgrades, renewable integration, and circular-economy measures to reduce both costs and emissions.