Music and Politics: Slo, Yu, 1980s

Martin Pogačar, PhD

CONTRIBUTOR

You know that feeling when a song floats on the radio, or through your headset, and you see and feel an event, or remember a scene, a scent from long ago? Music does that sometimes.

To paraphrase a famous politician, the later part of 20th century produced more music than we can possibly consume. Now-ancient tracks we have surreptitiously discovered on YouTube, or on old vinyl record, evoke in our minds the Zeitgeist of an era: that defining 1960s flower power, the glam of the 1970s, the grit of the 1980s, the now-nostalgic 1990s pop and Brit rock … The cacophony of sounds of the 2000s and 2010s, however, still await to be ascribed that musical something that we find period-defining and remember old times by. Of course, this point in time is still somewhere in the future, and not for us to know now just yet.

But we can always look back. The question I’d like to entertain here is: what is it that music reveals about its time of origin and what should we make of it? The 1980s seem just the right period to reflect on: far enough in the past to be felt remote, but for this very reason, relentlessly seeping into our present. A look at the music of the 1980s yields further interesting details through the perspective of the former Yugoslavia, a country that existed between 1945 and 1991.

For the readers young enough not to remember the times, or for those who know little about the period: the Yugoslav 1980s were a time of political and economic crises, of excessive shopping in Italy and Austria, when people were hoarding overpriced coffee and their cars were, well, lacking in fuel. Still, Yugoslavia was not tucked away behind the iron curtain in some type of boring self-isolation. Instead, the 1980s in these parts of the world were a period of musical experimentation, pushing the boundaries and crossing borders. It was also a period of political democratisation and, paradoxically, also of finding new limits. Politically, the decade represents a break in the histories of the post-Yugoslav region, the beginning of the end of one country and the prenatal phase of a bunch of new ones. Culturally, however, the 1980s have survived in numerous second-hand records and YouTube videos, and they keep defining the Slovenian political discourse. The 1980s are ingrained into the very fabric of post-1991 post-Yugoslav presents.

As it is true for any historical time, the 1980s also have their history, or historiography. In Yugoslavia, the decade inherited the legacies of the late 1960s – of student protests, of economic prosperity and the gradual liberalisation of the country, when the borders became increasingly permeable for both goods and people. In a time of Yugoslav Gastarbeiters migrating to Germany, the proverbial “red passport” was gaining currency. In musical terms, the 1960s followed global trends with beat music, folk, rock, and pop; the Mamas and Papas were successfully localised as Pepel in kri. The idiosyncratic genre of popevka (close to canzona or Schlager) flourished at music festivals, defining sound and age with the voices of Marjana Deržaj, Majda Sepe, Lola Novaković, and the poetics of Arsen Dedić. In line with cultural politics of Yugoslavia, rock was “let live” throughout the 1970s in order to blunt its potential subversiveness, by making it mainstream. Đorđe Balašević, Bijelo dugme, and a number of bands would take-and-adapt the musical form of revolt, and reflect it back to the famous days of Yugoslav heroic past. Some bands relished in such clear double perversion, say Buldožer, the alleged forefathers of punk. But after 1980, the year the Yugoslav President Tito died, we now know the country was heading for political crisis, exacerbated by the changes across the socialist world, and global economic strife.

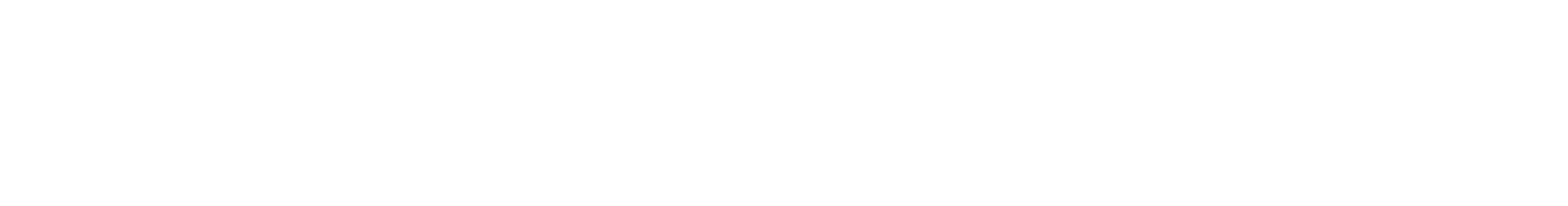

This was three years after the first punk-rock gig – at a school dance in Ljubljana, by a band called Pankrti – spawned a loud and unmerciful sonic expression of second-generation post-war Yugoslav youth. Members of Paraf, Lublanski psi, Niet, Termiti and others from across Yugoslavia, followed the trail of the irreverent Buldožer. Having had no personal experience with the Second World War, they found it difficult to fully identify with relentless presence of the legacies of war and their ideological grip. Much like their older peers from the 1960s, they glanced across borders and listened to “Western” popular music, watched films and read the literature, studied abroad, and bought records in London. They were faced with first-hand consequences of an idling regime failing to reinvent itself, and were fed up with it. And they showed it.

Listening to punk rock, it’s easy to imagine youth disappointment, the empty streets in the evenings, the dread of having nothing to do and nowhere to go, the fog and the cigarette smoke.

Po cestah hodijo ljudje [People walk down the streets].

Na vogalih bajt so zvočniki [Speakers hang off houses’ corners].

Koračnice se odbijajo od sten in jim sekajo glave [Military marches bounce off walls and cut off people’s heads]

Praznik. [Celebration.] (Otroci socializma, “Pesem za Mandič Dušana”)

The rough sounds of proverbial three-chord riffs, rudimentary basslines, and out-of-tune shouting give a background to the expression of disappointment, having detected an impasse:

Kje si zdaj, proleter, [Where are you now, proletarian]

kje je zdaj tvoja puška, [where’s your gun]

kje so zdaj tvoje roke, proleter. [where are your hands, proletarian]

Mi zdaj dvigamo zastave, [We’re raising the flags now]

v čast tvoje borbe, [to honour your fight]

vodi nas zdaj ti, proleter. [guide us now, proletarian]

Proleter, proleter, [Proletarian, proletarian]

zdaj v kamen vklesan si, proleter. [You’re carved in stone, now.] (Via ofenziva, “Proleter”)

In its early years, punk was a roar of a generation that wanted more, and wanted out of what it felt was a stifling grip of older generations even if it did not necessarily know how to do it and even if it did not necessarily seek a way out of socialism. It was the other side, of recalcitrant politics that cracked down on the youth for wearing crossed-out swastika badges, feverishly misinterpreted as endorsing Nazism. It was the critical element of the rising alternative movement, inherently fragmented and multidirectional, that housed a wide and varied assortment of civil society initiatives (gender rights activists, environmentalists, pacifists), artistic groups (NSK, Laibach), and engaged thinkers. The latter were quick to spot the political and cultural potency of the genre and of the social shift underway, and managed to make it a topic of wider discussion, followed by a series of talks and publications. It exposed a crack in the order of things.

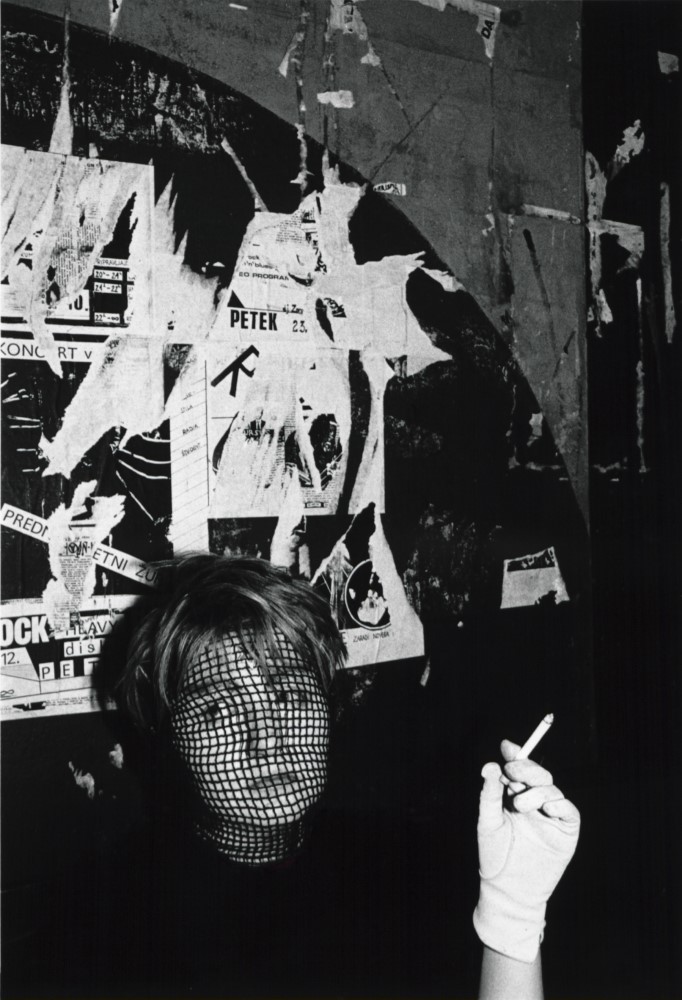

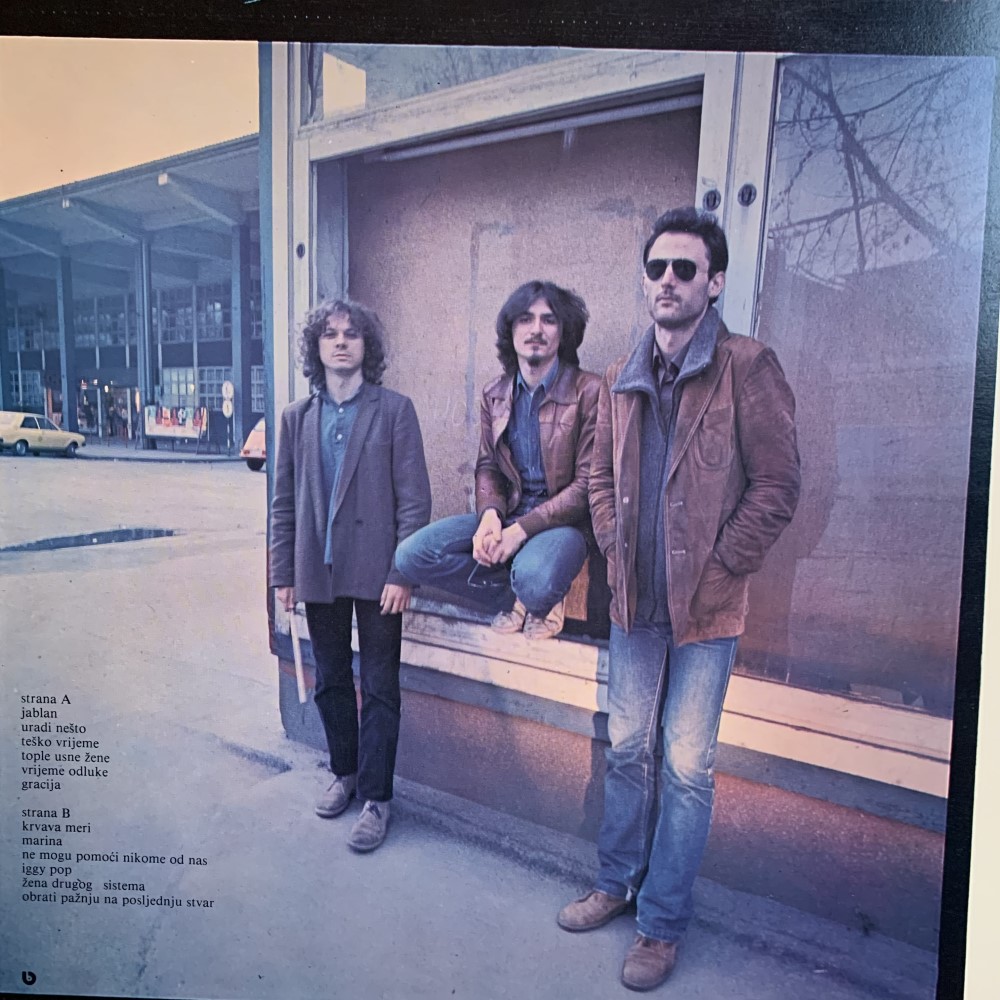

Somewhat later, this crack turned into what was then called “new wave”, which diverted music from the raw sounds of punk into a more elaborate combination rock and sometimes electro-industrial elements. Bands such as Ekatarina Velika, Videosex, Azra, Haustor, Disciplina Kičme, Denis & Denis, and others adopted a more sophisticated approach to music, elaborating on song composition and bringing in keyboards and electronic instruments.

At about the same time, however, popular music was rapidly evolving in other genres as well. Music production expanded, building on one of the strongest South-East European music industries, with festivals, bands, and labels such as ZKP RTV Ljubljana, Jugoton or PGP RTV Beograd producing domestic and issuing “Western” titles. The wide variety of bands and genres catered to increasingly profiled listeners, spanning narodnozabavna (newly-composed folk), rock, popevka, folk, disco, electro and industrial music, pop, punk, and new wave. The 1980s thus professed a differentiated music scene, including increasingly popular discs and clubs, both alternative and mainstream. Increasingly, all kinds of music made their way onto television and, through increasingly available and affordable record and cassette players, also into youth bedrooms and back to the streets. But as much as this was the time of awakening civil society and of the alternative, of punk and engaged art, it was also a time of rampant countryside pop.

And, with it, a time rising nationalism that found its foothold in wide segments of 1980s Slovenian society also through pop music. While alternative music and art arguably opened up the field for artistic and social experimentation, and actively thought politics, it was pop that managed to bank in on making fun out of the regime. The foremost group that built its popularity on fusing rock and rural countryside imagery, provocative and obscene lyrics, and playing with socialist iconography, was Agropop. The band’s frontman noted in 2012 documentary Nekoč je bila dežela pridnih (dir. Urša Menart): “We were a bit of an underground team, and we said, Slovenia is actually made of 90% rural population […] why the fuck should we sell some urban stuff if just a generation ago Slovenes were peasants?”. This sums up their credo, and also reveals the social tendency of moving away from the emancipatory alternative ideas of democratisation towards nationalism that started to prevail in politics, garnering support for the dawning independence project. A newspaper reported in 1988: “Their songs, as they say themselves, are a bit for fun, and a bit serious. Precisely due to their wide repertoire and merry atmosphere that they create with their songs, Agropop made it to the very top of the Slovenian music scene”.

The ambiguity enabled a profusion of ‘innocent’ nationalism that seems to have reached a milestone in 1987, when the band recorded an instant hit: “Samo milijon nas je” [There’s just a million of us]. The song repurposed the title of a Partisan poet Karel Destovnik Kajuh’s 1944 poem, “Samo milijon nas je” – written during Nazi occupation, it carried a charge of resistance and perseverance in face of imminent cultural and physical eradication by the occupying forces. Forty years later, Agropop put the first stanza to music and lyrically refurbished the song to a radically different historical context – and defined a different national enemy. But unlike Kajuh’s head-up-high poem that refutes the discourse of smallness, Agropop brought in a feel of self-victimisation:

Majhen narod vedno kriv je [A small nation is always guilty,]

Kdor je majhen, je vedno kriv [the small are always guilty,]

Če si majhen, bodi srečen, da si živ [If you’re small, be happy to be alive.] (Agropop, “Samo milijon nas je”)

And, with it, a time rising nationalism that found its foothold in wide segments of 1980s Slovenian society also through pop music. While alternative music and art arguably opened up the field for artistic and social experimentation, and actively thought politics, it was pop that managed to bank in on making fun out of the regime. The foremost group that built its popularity on fusing rock and rural countryside imagery, provocative and obscene lyrics, and playing with socialist iconography, was Agropop. The band’s frontman noted in 2012 documentary Nekoč je bila dežela pridnih (dir. Urša Menart): “We were a bit of an underground team, and we said, Slovenia is actually made of 90% rural population […] why the fuck should we sell some urban stuff if just a generation ago Slovenes were peasants?”. This sums up their credo, and also reveals the social tendency of moving away from the emancipatory alternative ideas of democratisation towards nationalism that started to prevail in politics, garnering support for the dawning independence project. A newspaper reported in 1988: “Their songs, as they say themselves, are a bit for fun, and a bit serious. Precisely due to their wide repertoire and merry atmosphere that they create with their songs, Agropop made it to the very top of the Slovenian music scene”.

These words implicitly evoke the feelings of subordination (internal imposition) and of political ineptitude, presaging the discourse that prevailed during post-socialist transformation and fuelled awkward ethno-exclusivism and cultural autarchy. This was quite different from the positive, band-aidish sound of “Svobodno sonce”, a song that musically accompanied “the nation” through the 10-day war of independence. The refrain paints, well, a utopia:

Sanjam deželo, ki pravični mir pozna, [I’m dreaming of a land that knows a just peace]

dolga je cesta, po kateri prideš tja. [It’s a long road to get there]

Ta pot je brez konca, a vodi naprej, [It’s an endless road, but it leads onward]

premnoga življenja ugašajo ob njej. [too many lives perish along the way.]

[ref] Svobodno sonce naj sije spet [Let the free sun shine again]

na to deželo in na ves svet. [to this land and all the world]

Svobodna pesem za vse ljudi [Let the freedom song for everyone]

topov grmenje naj preglasi. [Drown the cannon thunder.]

A popular memory and nationalist interpretation of events goes, it was to this song that the 1980s and Yugoslavia historically ended. Yet, it is also where the post-Yugoslav appropriation of the period began and can be witnessed even 30 years later, preventing history to be put to rest by daily political fights. But this is another story that, much like the present, will have to be told sometime in the future.

THE ADRIATIC

This article was originally published in The Adriatic: Strategic Foresight 2022

If you want a copy, please contact us at info@adriaticjournal.com.